Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise. Read online

Page 8

CHAPTER VIII.

_ONE INJUNCTION._

"I cannot leave you a great number of injunctions," exclaimed Mrs.Headley tearfully, on that last morning when all was ready fordeparture, and the day for the sailing of the steamer had really come.

"I think you have, mother," said Hugh, trying to hide his feeling undera joke.

"No, not to you, dear; to Agnes I may have."

"Yes, to _me_" said Hugh. "I am to mind Agnes, and not to mind John; andto mind I am kind to Minnie; and to keep in mind that Alice is youngerthan I; and to----"

"Shut up," said John; "we don't want to hear your gabble to the lastmoment!"

"I was going to say," resumed their mother gently, "that there was onething I did want you to think of."

"Tell us then, mother," said Alice, putting her arm round her fondly,"we'll keep it as the most important of all."

There was a momentary silence, and then Mrs. Headley turned to herhusband with a mute appeal. "Tell them," she said brokenly, "what wewere saying this morning."

"We want you all to think of one thing. In _any_ difficulty, in _every_difficulty, in _all_ circumstances, say to yourselves, 'Lord, what wiltThou have me to do?' If you wait and hear the answer, it will help youin everything."

"People generally do wait to hear the answer to their question, don'tthey, father?" asked John.

"Not always; especially when they are speaking to God. But you be wiser,my children. In the waiting-time for the answer an extra blessing oftencomes."

The children looked thoughtful; and then their father took from a papera large painted card in an oak frame, which he proceeded to hang up on anail ready prepared for it.

On the card were letters in crimson and gold and blue, and the childrenread:

"Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?"

Then the sound of wheels suddenly reminded them that the parting hadcome. With a close embrace to each from their mother, and with anearnest "God bless you" to each from their father, the travellers turnedto the door, followed by John and Hugh, who were to accompany them tothe railway station.

When the last bit of the cab had disappeared. Agnes turned round to heryounger sisters and put her arms round them both lovingly. "We'll beever so happy together when we once get settled in," she said, chokingdown her own emotion, and bending down to kiss them in turn.

"Oh, yes," answered Alice with a sob, trying to look up bravely.

But Minnie could not look up. Her mother was her all, and her mother hadgone. She threw herself into Agnes's arms in a passion of misery.

Agnes sat down and tried to make her comfortable on her lap; but thechild wailed and sobbed, and gave way to such violent grief that theelder sister was almost frightened, and looked towards the window with amomentary thought of whether it would be possible to recall her mother.

It was only momentary, for how could she? Then her eyes fell on the newtext, and her heart, with a throb of joy, realized that the Lord waswith her.

"Always," she said to herself; "so that must mean to-day. 'Lord, whatwilt Thou have me to do?'"

She bent her head over the little golden one, and clasped her armstighter round the trembling little form, and then she said softly:

"Minnie, have you read our text since father and mother went?"

Minnie listened, but only for an instant, then she sobbed louder thanever.

"Minnie," again pursued Agnes, "do you think you are carrying out what_He_ would have you do?"

Minnie stopped a little, and clung more lovingly than before to hersister's waist.

"We must be sorry they are gone; we can't help it, and I don't thinkJesus wants us to help it; but we ought not to give way to such grief asto seem rebellious to what He has ordered."

"Do you think I am?" asked the child brokenly.

"What do you think yourself?"

"I don't know," hesitating.

"Well, think about it for a moment. Look here. Minnie, I want to put upthese things that are scattered about, so I will lay you on the sofa andcover you up warm; then you can think about it while you watch me. Come,Alice dear, you and I shall soon make things look brighter if we try."

Alice had been standing gazing rather forlornly at Minnie, but nowturned round with alacrity. To do something would divert her sorrowfulthoughts.

By-and-by a heavy sigh from Minnie made her sisters look at her. Thereshe lay like a picture, her long curls tossed about over the sofacushion like a halo, her dark eyelashes resting on her flushed cheeks,where the tears were hardly dry, asleep.

"What a good thing," said Alice in a low tone. "I thought she would cryherself ill."

"Yes, I am glad," answered Agnes, looking down upon her. "But, Alice,the boys will be back before we have done if we stand talking."

"Then we won't. Agnes, did not aunt Phyllis say she would come inearly?"

"Yes; but I hope she will not till we have put away everything. Justtake up that heap and come upstairs with me, Alice; and then run downfor that one, will you? You don't mind?"

"I'm not going to 'mind' anything, as Hugh says," answered Aliceearnestly, a tear just sparkling in the corner of her eye.

"That's a dear girl; it will make everything so much easier if you dothat."

"I mean to try."

They left the room, closing the door after them, and went up with theirloads--papers, string, packing-canvas, cardboard boxes, rubbish, shawls,and what not.

Agnes placed the various things in their places, while Alice watched andhanded them to her, and at last all was done and the girls ran down,just as a double rap sounded through the hall.

"That's auntie's knock, I shall open it," exclaimed Alice, and in amoment she admitted a little lady, whose pale delicate face and stoopingattitude betokened constant ill health.

"Well, my dears," she said cheerfully, "I knew you would have a fewthings to do after such an early starting, so I waited for a littletime. Are the boys back yet?"

"No; we expect them every moment," answered Agnes, leading her aunt intothe now orderly dining-room, and placing her in an arm-chair.

Miss Headley's eyes wandered round in search of little Minnie, and soonshe saw the sleeping child.

"Not ill?" she asked, reassuring herself with her eyes before Agnesanswered:

"She was tired with excitement, I think, and grief. I am so glad she isasleep."

"The best thing for her. And they got off well?"

"Oh, yes; but I hardly knew how utterly dreadful it would be to feel Icould not call them back!"

Agnes turned away; she could not say any more. While the responsibilityrested on her alone she had been brave, but now with her aunt's sympathyso near she began to feel as if she must break down.

"I know," said the soft voice, "do not mind me, my child; come here andlet me comfort you."

Agnes knelt down and laid her head on her aunt's shoulder, while one ortwo convulsive sobs relieved her burdened heart.

"There will often be moments when you would give anything to have themhere, my child; but the Lord knows just that, and has sent forthstrength for thee to meet it all. We never know how very dear andprecious He can be till we've got no one else."

"I shall learn it soon," whispered Agnes.

"Yes, my child; and it is such a mercy to know that He suits ourdiscipline to our exact need. The other day I was on a visit in thecountry, and had to go to an instrument-maker there to do something formy back. He told me he could not help me at all, for my case was so verypeculiar, and he had nothing to suit me. But that's not like the Lord,my child. He knows us too intimately for that. He does not think ourcase too peculiar for His skill, but holds in His tender hand just thesupport, just the strengthening, just the treatment we want, and Hegives us what will be the very best for us."

Agnes and Alice knew to what their aunt referred. An accident when shewas a beautiful young woman of twenty had caused her life-longsuffering, and obliged her to wear a heavy instrument which often gaveher great pain and weariness

.

Her niece raised her hand at those gentle words, and stroked her aunt'sface lovingly.

"It is resting to know He understands perfectly, my child, isn't it?"

"Very. But oh, auntie, I wish you hadn't to suffer so!"

"Don't wish that, my dear, but rejoice that, in every trial that hasever come to me, I can say, 'His grace has been sufficient for me.'"

Agnes knelt on in silence; and aunt Phyllis did not attempt to disturbthe quiet till some hasty footsteps were heard along the pavement, whichcame springing up the steps, and in another moment the two boys, freshfrom their walk, came bursting into the room; but not before Agnes hadsprung up and seated herself at the table with her work.

"Hulloa, Agnes! Why, auntie, is that you? So you've come to look afterthe forsaken nest, have you?"

"How did they get off, John?" Agnes asked, looking up as quietly as ifshe had been sitting there for an hour.

"Very well; mother was cheerful to the last."

"And they had a foot-warmer?"

"Your humble servant saw to that."

"And you got them something to read?"

"Wouldn't have anything."

"And they did not leave any more messages?"

"None whatever. Now, Hugh, as Agnes has pumped me dry, let Alice take aturn at _you_!"

Alice, till her brothers came in, had been leaning over the fire, deeplyburied in a book and now turned round to it again, as if she would verymuch rather read than do anything else.

Hugh seeing this, advanced a step nearer, and his eyes lookedmischievous.

"Well, Alice, don't perfectly smother a body with questions. One at atime. What's the first?"

"I don't know; I haven't any to ask."

"You mean you're too busy?"

"No," answered Alice, half vexed.

"Perhaps you're cold, you're such a long way off from that tiny fire!"

"I'm not cold," said Alice, putting her hand up to her glowing face.

"Not? Now I really thought----"

But a gentle voice interrupted what was becoming too hot for poorAlice's temper, and aunt Phyllis said:

"Grandmama invites you all to dinner to-day, my dears, at two o'clock;will you come?"

At the word dinner Agnes started. "Oh dear, auntie, I forgot it was myduty now to see after dinner! I do not believe I should have thought ofit for ever so long."

"Cook would have reminded you, I dare say," said her aunt, smiling.

"What are you boys going to do this morning?" asked Agnes.

"I'm going to my room to have a general turn out for the holidays, andshall not be visible again till five minutes to two."

"That's a good thing," said Agnes, laughing.

"Your politeness is only exceeded by your truth," said John, giving hisaunt a kiss, and disappearing through the door before Agnes could givehim back an answer, had she wished it.

"And what is Hugh going to do?" asked Miss Headley, turning to him.

"Tease Alice," said Hugh, nodding towards the crouching figure by thefire.

"I was going to say that I have to go to see a woman in Earl Street, andwanted you to carry my basket for me, Hugh. Can you spare time, do youthink?"

"All right, auntie."

"Where's Hugh going?" said Minnie, sleepily, opening her eyes.

"He is going out with me, darling; would you like to go too?"

"I don't know; I think I'm going to sleep again."

She turned her back on the room, and vouchsafed no further notice of heraunt, nor of anyone else. Agnes gave a glance of apology, but MissHeadley answered by a look that it was not needed, and in a few momentstook her leave, followed by her nephew, who ran in next door for thebasket, and caught her up before she had reached the corner of thestreet.

Agnes left the room, and Alice woke up from her book to find herselfalone.

She was just going to stoop again over it, when her eyes caught theunaccustomed frame upon the wall, and she could not but see the words,"Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?"

"I've nothing to do but this now," she said, drawing her shouldersnearer to the blaze. "It's holiday time, and I have not lessons orduties of any kind; I may do as I like."

But though she tried to read, she could not forget that question. Atfirst she determined to shake it off, but by-and-by her book fell closedon to her lap, and she looked up straight at the words, thoughtfully.

"This is the first way I am keeping my resolves; a pretty way!"

"Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?"

Then she waited, as her father had said--waited, looking at the words asif they would shine out with an answer. And so they did; for as her eyesrested on the last word, she suddenly started up.

"Do," she said, half aloud. "I don't suppose He likes me to sit hereidling my time. I wonder if Agnes wants me? Or if not, I promised motherto practise a whole hour every day, and as I am going out to dinner Ishall have to do that first."

Then her eyes met Minnie's wondering ones shining out from among thegolden curls and crimson sofa cushion, and she heard a little voice say:

"Who wants you to '_do_'?"

Alice pointed with her finger towards the text.

"Oh!" said Minnie, comprehending.

"But I didn't remember you were there, or I should not have spokenaloud."

"I forgot what Agnes said, because I went to sleep; but----"

"Yes," answered Alice, waiting for what the little pet sister wanted tosay.

"I don't think He would have liked me to cry so _much_, if I had askedHim first."

And with another little sob she rushed past her sister and flew up thestairs.

At five minutes to two o'clock, John opened his bedroom door and calledAgnes.

She was just coming out on the landing, with her hat on, followed byMinnie and Alice.

"Come and see my arrangements," he said, opening the door wider.

"I don't see anything particu----Oh!" with a start, "why, John, wheredid you get that?"

"Out of these two hands of mine, to be sure, and these eyes, and thatpaint box, and that cardboard."

On the wall hung the same text that their father had prepared with suchcare downstairs, only that John's was not framed, but put up with foursmall nails.

"I thought I should see it more up here than downstairs."

"And he thought," added Hugh slyly, "that _I_ should have the benefit ofit here."

"I never thought of you at all," said John.

"It is very nice," said Agnes, coming in to examine it.

The others went down stairs, and the brother and sister were left alone.

"I've been thinking a lot, Agnes," said John, turning his back to her,as he busied himself at one of his drawers, "and I've made up my mindwhile I've been tracing the words of that text."

"What about?" asked Agnes, with a feeling that there was somethingunusual in his tone.

"I've determined to take it as my life text."

"John!"

"Yes. It seemed so horrid without mother, and I've been thinking aboutit, on and off, for a year past; and to-day, as I painted those words. Ithought----"

Agnes was standing behind him, her soft cheek resting against the backof his shoulder.

"Yes," she whispered.

"He seemed to say to me, that the first thing I had to _do_ was to cometo Him."

"I'm _sure_ it is."

"So now you know," said John huskily.

"And you did come?" asked Agnes, feeling as if she wanted to understandall before she could rejoice.

"Of course," answered John, turning round astonished; "I should not havesaid a word if that had not been the end of it!"

Goody Two-Shoes

Goody Two-Shoes The Pearl Box

The Pearl Box And when you gone...

And when you gone... Stranger At The Other Corner

Stranger At The Other Corner My Young Days

My Young Days Harry's Ladder to Learning

Harry's Ladder to Learning Vice in its Proper Shape

Vice in its Proper Shape_preview.jpg) Promise (the curse)

Promise (the curse) The First Sexton Blake

The First Sexton Blake Golden Moments

Golden Moments Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3 The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Phebe, the Blackberry Girl

Phebe, the Blackberry Girl Stoned Immaculate

Stoned Immaculate Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3 The Wonder of War on Land

The Wonder of War on Land Breaking Bailey

Breaking Bailey The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience

The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience The Popular Story of Blue Beard

The Popular Story of Blue Beard The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service

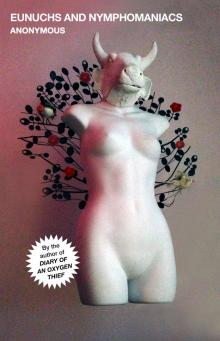

The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs

Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3 Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories

Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories Two Yellow-Birds

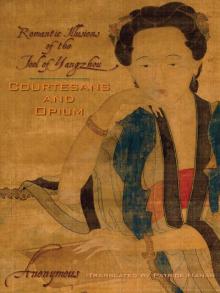

Two Yellow-Birds Courtesans and Opium

Courtesans and Opium The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest

The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest Toots and His Friends

Toots and His Friends Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield

Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City

Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City A Picture-book of Merry Tales

A Picture-book of Merry Tales The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago

The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria

Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm

The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog

Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog The Story of the White-Rock Cove

The Story of the White-Rock Cove Grushenka. Three Times a Woman

Grushenka. Three Times a Woman Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself

Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself Falling in Love...Again

Falling in Love...Again The Colossal Camera Calamity

The Colossal Camera Calamity Child of the Regiment

Child of the Regiment Elimination Night

Elimination Night The Kingfisher Secret

The Kingfisher Secret Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise.

Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise. The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn

The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn Adventures of Bobby Orde

Adventures of Bobby Orde Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries

Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries When Love Goes Bad

When Love Goes Bad The Incest Diary

The Incest Diary Calling Maggie May

Calling Maggie May The Infidelity Diaries

The Infidelity Diaries Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) ARABELLA

ARABELLA The Eye of the Moon

The Eye of the Moon Dara

Dara THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake

THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake The Book of Death

The Book of Death The Book of David

The Book of David The Devil's Graveyard

The Devil's Graveyard The Book With No Name

The Book With No Name I Am A Lesbian

I Am A Lesbian Njal's Saga

Njal's Saga The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh Darling

Darling Tal, a conversation with an alien

Tal, a conversation with an alien Go Ask Alice

Go Ask Alice Aphrodizzia

Aphrodizzia The Campus Trilogy

The Campus Trilogy Augustus and Lady Maude

Augustus and Lady Maude Lucy in the Sky

Lucy in the Sky Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Pleasures and Follies

Pleasures and Follies The Red Mohawk

The Red Mohawk A Fucked Up Life in Books

A Fucked Up Life in Books Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) Astrid Cane

Astrid Cane BEATRICE

BEATRICE The Song of the Cid

The Song of the Cid