The Infidelity Diaries Read online

First published in 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 9208

eISBN 978 1 74343 637 0

Internal design by Christabella Designs

Typeset by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Extracts from The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini © Bloomsbury Publishing UK

The characters and events of this story are entirely fictional. Characters described in this book are not based on any real person whether living or deceased and any similarity is purely coincidental.

CONTENTS

ZARA

LILI

EVE

Zara

She was standing at the end of the hall in the late afternoon light, her back arched against the wall, between two landscape paintings. Closing her eyes, she ran her hands up and down the red dress clinging to her curves. The dress had been designed by a genius. Its neckline was low enough to be provocative, but the hemline was below knee-length—too long for Leo, the husband of our hostess, to commit adultery there on the spot. But he was still open to temptation, breathing hard in a fashion that suggested he’d been just about to grab her.

Both of them saw me at the same time.

He froze. His seducer laughed.

‘The bathroom’s just opposite us,’ she said, without any sign of embarrassment. ‘Leo was just showing me around, weren’t you, Leo?’

Leo muttered something about needing to check his voice messages, and fled.

There was nothing for me to do but walk into the bathroom as if nothing had happened, although I was hoping that she would be gone by the time I came out.

But she hadn’t gone. She was still there, smiling at me and wiggling her shoulders and breasts in some sort of performance over which she had no control; only right at this moment it was also an act of supreme mockery—and intent—as both of us knew perfectly well.

The canoe came from behind one of the towering limestone peaks in the sea off southern Thailand. There were only two occupants aboard: the boatman, and a woman too far away to see clearly, who was holding a pair of binoculars up to her eyes. I watched as she turned and spoke to the figure paddling behind her, pointing an arm in our direction—and within seconds the canoe started heading straight for us.

Even today, writing this in the country where I live now, it’s difficult to describe the sense of dread I felt at that moment. I was so overwhelmed that I thought I was going to faint, but not realising what was occurring, I put it down to the fierce afternoon heat. It was impossible to imagine in such an enchanted setting a malevolence that was about to change the course of our lives.

In retrospect, I believe that what I experienced was more than instinct: it was foresight. The ability to believe in the mysterious has no place in our rationalist society, but I have no doubt what happened that day verged on the unreal. It was purely a physical sensation. I didn’t ‘see’ into the future, or connect the sense of dread that I felt with the woman travelling in the canoe. And only very gradually, over a few years, would I realise how damaged she was.

Sergei, my Russian husband, and I were in Thailand on holiday in December 2005. We were staying at a hotel close to Phang Nga Bay, which is where this story begins. On the afternoon in question, we’d set off on an old Thai boat with a huge wooden hull, crewed by a group of genial locals, to explore the stretch of water best known for the peaks and islets rising vertically from this corner of the Andaman Sea.

We sailed for almost an hour into the bay until we reached a cluster of the giant rock formations that, from a distance, looked like mountains separating our world from another just beyond. There were sea caves hidden in the shadows of some of the islets, which we wanted to see close up. The crew dropped anchor and we climbed into one of the canoes that had been provided for us, accompanied by a young Thai man who spoke broken English and was acting as our guide.

It was only once we were on the water that we began to get a real sense of the scenery around us. As our guide turned the canoe towards a majestic islet close by, dozens of monkeys began scrambling down the cliff face to a sunny ledge close to the water. There, they lined up in a row—like a council of ancients—eyes fixed on the strangers approaching.

We asked our boatman if we could just drift for a while under the gaze of the primates, and he nodded and smiled. From under his seat he produced bottles of mineral water. ‘No ice!’ he joked, handing a bottle to each of us.

It’s pointless wondering what would have happened if we hadn’t taken that decision to drift along the base of the cliff, and instead had paddled into one of the sea caves, then out the other side and gone on back to the boat. In all likelihood, we would never have encountered Caitt coming around that limestone peak.

The dramatic beauty of Phang Nga Bay made the moment more vivid. But we were going to meet her sooner or later, if not in Thailand, then in Sydney where we all lived.

Neither Sergei nor I was born in Australia. I was seventeen when I moved to Sydney from Canada in 1977 with my parents and two slightly younger sisters, Lili and Eve, and our older sister, Lori. Sergei, an architect, was from Moscow. His parents had managed to get him and themselves out of the Soviet Union in 1973 after the emigration policy had eased. Most of those allowed to leave were ethnic Jews. But Sergei’s father, a history teacher, had been in trouble with the authorities for encouraging his students to read the work of ‘dissident’ writers. They were glad to get rid of him, Sergei always said. He was twenty-two years old when he left the Soviet Union and, with his parents, went to live with a relative in London. There, they became part of the Russian diaspora and he enrolled in architecture studies.

The two of us met in 1983, on a ferry that was going to Tallinn, the capital of Estonia—then still under Soviet occupation. I always liked the fact that we met in a part of the world that was out of the ordinary and even a little mysterious.

Sergei was visiting the land where his mother was born. I was fulfilling a dream of spending part of the European summer in Finland, in the Land of the Midnight Sun, where I’d been invited to stay with old family friends in Helsinki.

These friends threw a party for me one evening in their huge old apartment in the Kruununhaka district, which is in the oldest part of the city, next to the sea. One of the guests arrived with a Swedish visitor, who told me he did ‘business’ in Tallinn. He was intentionally enigmatic; I was young, and didn’t ask questions. After dinner we sat on the ancient balcony and talked.

In a city where it’s still light at 10 p.m. for a couple of months a year, anything seems possible. So when he suggested that, instead of going to Lapland, I should travel behind ‘The Iron Curtain’ and see life in a country run from afar by the Kremlin, I agreed. Estonia was just a ferry ride away, across the Gulf of Finland, and foreigners were allowed to

visit—although they couldn’t go outside Tallinn. I planned to meet him there in a week’s time.

Then fate intervened.

The Swede got my arrival day wrong. I only learnt this a long time afterwards and by then I’d almost forgotten him altogether. Sergei was on the ferry to Tallinn, and struck up a conversation with me soon after we sailed. At twenty-three, I was a hopeless romantic. Sergei, at thirty-two, seemed very worldly and had an enchanting Russian accent to boot.

And so, thanks to that missed rendezvous in Estonia, here I was, almost twenty-two years later, sitting in a canoe off the Thai coast, watching the woman who was about to carve her initials over our marriage approaching us over the flat, pale blue sea.

As she began to close the distance between us, Sergei suddenly said, ‘I think I know who it is.’

The moment he said this, I knew—although I can’t explain how—that our life had just jumped tracks.

‘Who?’ I asked, still battling what I thought was heatstroke. I opened the bottle I was holding and sprinkled some of the water over my face.

‘Caitt. Joe’s sister-in-law,’ replied Sergei. ‘It is her,’ he added, squinting into the sun at the blonde who was now waving—at both of us, as I first thought.

Joe was an English friend of Sergei’s from London, who had also graduated in architecture. He came to visit us in Sydney in the mid-1980s, and liked the city so much that he decided to emigrate to Australia. The two of them had often discussed setting up an architecture practice together, although I think they were both happier working alone.

We never knew that Joe, whose wife, Sally, was a good friend of mine, had a brother who had also moved to Sydney. The first we heard of his existence was when Sergei said that we were going on holiday to Thailand, whereupon Joe mentioned an older sibling, Michael, who had left for Thailand the previous week. He was a yacht broker, married with no children, and was travelling with his wife and a friend of theirs, a film editor called David.

Another coincidence. We knew David casually. He lived in our street.

When Sergei mentioned that we’d booked into a quiet hotel on the northwest coast of Phuket—far from the tourist-trap towns on the island—Joe laughed.

‘That’s where they’re staying as well,’ he’d replied. ‘God, what a coincidence!’

So we were definitely fated to meet. That much is clear.

Joe explained later that his brother and Caitt, who was South African born, had only recently moved back to the city from a small town in the New South Wales Southern Highlands where they’d been living for years, which explained why we hadn’t met them before.

Soon after this conversation we left for our holiday. We didn’t expect to meet Joe’s brother and sister-in-law immediately, but on our first day at the hotel in Thailand, Sergei ran into David during a brief trip back to our room. I wasn’t with him; I was already in the sea, swimming.

David introduced Sergei to Michael and Caitt, who were there in the lobby with him. They were all waiting for a taxi to take them to the airport, he explained. Caitt wanted to spend some time in Bangkok, and Michael and David had decided to go with her. Plans were made on the spot for us all to spend an evening together when they got back at the end of the week.

When Sergei returned to the beach, he told me Caitt was a speech pathologist who worked with autistic children.

‘She sounds interesting,’ I commented. But there the subject had rested. We hadn’t talked about the trio again.

‘I remember now,’ Sergei said, as the canoe carrying Caitt glided towards us, ‘they were due back last night. I wonder where the others are.’

‘Perhaps they’re on that big tourist craft we passed a little while ago,’ I replied.

I’d barely finished speaking when the monkeys that were lined up on the cliff ledge behind us became unusually agitated. Some covered their eyes with furry arms and started screeching. Others scrambled away, vanishing over rocks into the cave beyond.

See no evil? That thought only occurred to me many years later.

Then Caitt’s canoe came up alongside and I felt nothing but emptiness. I cannot explain that either.

Women know women. We’re meant to have a radar that goes off when predators slink—or sail with bare legs—into view. Was this super-instinct the reason for my feeling of emptiness and my sense of dread a few minutes earlier? I’d never had such a reaction to a woman before, so perhaps it was.

‘Sergei! Hello! Imagine running into you all the way out here!’

The stranger, as she still was, spoke in a merry tone while shielding her eyes with one hand. In defiance of the sun, she was wearing neither sunglasses nor hat, and had on a loose yellow shirt that came to the top of her knees.

She looked straight at Sergei as she spoke, without acknowledging my presence. This was my immediate impression of her: that she was shutting me out. My second, strongest impression was the intensity of that stare. Anyone else observing the scene might have assumed that she and Sergei were already lovers, and that this bizarre meeting off the Thai coast was no accident.

As I would learn soon enough, the intense stare and the melting look were two of Caitt’s specialties—though not ones that she ever practised on women. She kept her eyes fixed on Sergei as he reached out and held the side of her canoe with one hand. At this point, she and I were literally sitting side by side.

‘How did you come to be out here?’ he said. ‘You’re not stalking us by any chance?’

Caitt laughed.

Pale skin with freckles. Pink lipstick. Early to mid forties—we were about the same age.

Still no eye contact with me.

Another large pleasure cruiser appeared from around one of the peaks, creating a series of small waves. As the ripples of water swept towards us, our two boatmen took over, keeping the canoes steady and then talking quietly together in Thai. One had a gold ring in his ear, and both of them wore bandanas tied around their heads, like pirates. It was a good day for a kidnapping.

Sergei, completely oblivious to the lack of communication between Caitt and myself, leaned forward as he slipped an arm around my waist.

‘This is my wife, Zara. Zara, this is Caitt.’

Somewhere close by there was a soft splash. There were flying fish as well as turtles in these waters, although we hadn’t seen any turtles as yet.

Then everything became still. The monkeys stopped screeching. The breeze died. The heat intensified.

Caitt had stopped laughing.

She was staring at Sergei’s hand on my hip. Maybe it was a trick of the light, but she looked furious. As I watched, her mouth started to spasm and I thought she was going to be ill. All of this lasted only a couple of seconds, but it was startling to see.

Sergei, meanwhile, had continued talking in his affable manner. ‘This is our first holiday for ages. Zara works too hard. I told her we only had a three or four month window before the wet season starts.’

Only at this point did Caitt look directly at me for the first time. Her face had become totally expressionless.

‘Oh yes,’ she remarked, in a tone of indifference. ‘Joe said that you write biographies. I haven’t read any of them, I’m afraid.’

By now she had under control whatever it was that had affected her before and perhaps for this reason showed little interest in taking the conversation with me any further. So I gave her a head start.

‘Sergei said you work with autistic children.’

Silence.

‘That must be very demanding, but very satisfying,’ I went on.

No reaction.

The heat was getting to me. I felt like diving into the sea. Why was conversation with this woman so difficult? Why was she so strange? Where was the breeze?

There was another splash from a flying fish and then, far in the distance, the sound of thunder.

Finally, Caitt spoke.

‘Yes, it is satisfying,’ she said. ‘I work with a team of speech pathologists three days

a week. The rest of the time I try to pursue other interests. I did a three-month gourmet cookery class last year, and I’m thinking of taking art classes. A rigid lifestyle isn’t my thing. I’m not locked into a career like you, with no time for anything else.’

The first soft slap across the face.

I replied that I wasn’t sure any writer had a ‘career’, since writing falls into a category of its own. Most writers would argue this, I added.

Caitt smiled as if I’d said something amusing. ‘But don’t you churn out popular biographies?’ she inquired. ‘It would be harder if you had children.’

I ignored this remark. My sadness at not having children was private, and besides, Caitt didn’t have children either. I explained that I had a contract with a publisher to produce two short-form biographies a year, although they still needed to be informative and well written. But I was starting to feel tense.

Why should I have to justify my work?

She wasn’t going to give in.

‘Joe said you’re always working and that you’re often away. I seem to remember you were in your room working the day we met Sergei in the hotel.’

‘I was swimming,’ I replied.

‘I did tell you that,’ interrupted Sergei, sounding puzzled as he addressed Caitt.

‘So you did. I forgot. I must have got the wrong impression of Zara.’

Never has an apologetic remark been so loaded.

And then she smiled, and changed the subject.

‘I’d like to invite you over for Sunday lunch when we get back to Sydney. You live very close to us, I think.’

You . . . Singular? Plural?

‘Spasibo,’ Sergei thanked her. ‘Zara and I accept your invitation to lunch with pleasure.’

He may as well have not added that last sentence, since Caitt started talking well before he had finished.

‘I’m going back to Sydney tomorrow,’ she announced. ‘Some family friends have had a skiing accident. They’ve each broken a leg and they need help with the children. I’m going to fill in until a relative takes over in a few days. They live close to where we are so I can go back and forth as I need to. We were due to go back at the end of this week anyway, so it’s not a big problem. Luckily the airline won’t charge me extra.’

Goody Two-Shoes

Goody Two-Shoes The Pearl Box

The Pearl Box And when you gone...

And when you gone... Stranger At The Other Corner

Stranger At The Other Corner My Young Days

My Young Days Harry's Ladder to Learning

Harry's Ladder to Learning Vice in its Proper Shape

Vice in its Proper Shape_preview.jpg) Promise (the curse)

Promise (the curse) The First Sexton Blake

The First Sexton Blake Golden Moments

Golden Moments Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3 The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Phebe, the Blackberry Girl

Phebe, the Blackberry Girl Stoned Immaculate

Stoned Immaculate Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3 The Wonder of War on Land

The Wonder of War on Land Breaking Bailey

Breaking Bailey The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience

The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience The Popular Story of Blue Beard

The Popular Story of Blue Beard The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service

The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs

Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3 Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories

Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories Two Yellow-Birds

Two Yellow-Birds Courtesans and Opium

Courtesans and Opium The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest

The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest Toots and His Friends

Toots and His Friends Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield

Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City

Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City A Picture-book of Merry Tales

A Picture-book of Merry Tales The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago

The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria

Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm

The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog

Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog The Story of the White-Rock Cove

The Story of the White-Rock Cove Grushenka. Three Times a Woman

Grushenka. Three Times a Woman Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself

Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself Falling in Love...Again

Falling in Love...Again The Colossal Camera Calamity

The Colossal Camera Calamity Child of the Regiment

Child of the Regiment Elimination Night

Elimination Night The Kingfisher Secret

The Kingfisher Secret Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise.

Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise. The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn

The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn Adventures of Bobby Orde

Adventures of Bobby Orde Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries

Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries When Love Goes Bad

When Love Goes Bad The Incest Diary

The Incest Diary Calling Maggie May

Calling Maggie May The Infidelity Diaries

The Infidelity Diaries Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) ARABELLA

ARABELLA The Eye of the Moon

The Eye of the Moon Dara

Dara THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake

THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake The Book of Death

The Book of Death The Book of David

The Book of David The Devil's Graveyard

The Devil's Graveyard The Book With No Name

The Book With No Name I Am A Lesbian

I Am A Lesbian Njal's Saga

Njal's Saga The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh Darling

Darling Tal, a conversation with an alien

Tal, a conversation with an alien Go Ask Alice

Go Ask Alice Aphrodizzia

Aphrodizzia The Campus Trilogy

The Campus Trilogy Augustus and Lady Maude

Augustus and Lady Maude Lucy in the Sky

Lucy in the Sky Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Pleasures and Follies

Pleasures and Follies The Red Mohawk

The Red Mohawk A Fucked Up Life in Books

A Fucked Up Life in Books Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) Astrid Cane

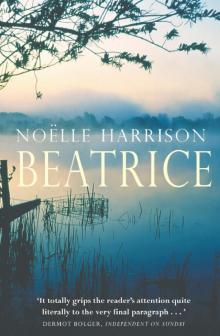

Astrid Cane BEATRICE

BEATRICE The Song of the Cid

The Song of the Cid