The Infidelity Diaries Read online

Page 7

The still-frail figure of Lori in her hospital bed.

In the end it was Mum who had insisted—as Dad told me—that I must go overseas as planned. Eve was about to return to Sydney. Lili would come back as soon as she could. I would be away for only ten days.

Even Lori, smiling weakly, had told me that I must do my work.

Still, Sergei must have been anxious that I might be planning to stay away longer than planned, because he rang that morning soon after I got to the eyrie. I didn’t pick up. Nor did I answer when he rang an hour later. Or when he rang at midday.

I wasn’t punishing him by not taking his calls. I literally didn’t know what to say to Sergei anymore. I had no idea what he was thinking, or doing, or planning.

I suspect that my not answering the phone was also emotional exhaustion, the result of having Caitt in the background for so long, chipping away at the task of separating Sergei from me with the sort of patience that only someone fanatically committed to the destruction of our relationship could maintain.

At 3 p.m., when I finally picked up the phone, there was no mistaking the panic in Sergei’s voice. ‘Don’t stop talking to me,’ he said. We had a civil conversation, although I can no longer recall what we spoke about.

Then I drove to the hospital, and didn’t get home till 9 p.m. Both Sergei and I were tense with each other. Despite needing to pack and get to bed reasonably early, I felt that we should talk about what was happening. But Sergei said it was too soon; we’d discuss everything once I was back. I was beginning to feel anger again—and I didn’t want to be angry. I didn’t want to have feelings about anything.

‘Don’t worry. I won’t phone for the whole ten days I’ll be gone,’ I said before I left for the airport early the following morning.

‘Then I’ll ring you,’ he retorted.

Sure enough, he rang several times, concerned for my safety because I was in a dangerous part of the world. The calls had to be brief. It was only when I got back that he told me how worried he’d been. ‘I assume that you saw Caitt every night all the same,’ I replied.

Sergei told me that whether he’d seen Caitt or not was none of my business. Later, though, he mentioned that he’d told Caitt—to her chagrin—that he remained very attached to me. ‘What was the context of the conversation?’ I asked.

But to this, Sergei didn’t reply.

Far harder for me to accept was the explanation that he eventually gave me, as part of his justification for having an affair with Caitt: that he still loved me but, having just confronted mortality, he needed to experience again the same level of sexual passion that comes with a new relationship. In other words, we had been together for too long—and life was unpredictable. And short.

He then said that Caitt had confided to him after he’d come out of hospital that she’d long hidden a terror of sudden, serious ill-health. Ten years earlier, she’d been diagnosed with a brain tumour; luckily, it was benign. But the experience had frightened her badly. As Sergei told it, she had stressed to him that because they had both seen death on the horizon, this set them apart from other people. The normal rules didn’t apply to them. They could have an affair in the knowledge that everything was permissible, and should be. She said nothing about how she would have reacted to the same situation if she was in my shoes, although I had a fairly good idea, given her abnormal possessiveness of Sergei.

‘And you agree with her?’ I asked him now, of her so-called philosophy.

‘It isn’t a matter of agreeing or disagreeing,’ he replied, and went on to talk about the new urgency he felt to seize opportunities—like finding passion again. Caitt was offering him that opportunity, he added.

We were sitting in our courtyard when this conversation took place. The bougainvillea that Sergei had planted at the back of the house looked glorious that year, although it was beginning to spread over the roof and badly needed pruning. Anyone seeing us with our glasses of wine, sitting in its shade that particular afternoon, would never have guessed what we were discussing. Or rather, what Sergei was telling me, since I listened in silence.

There was a reason for this. I understood what Sergei was saying. I even understood his need for a ‘last chance’. I still do. These days, whenever I hear of someone whose relationship has foundered following a potentially fatal illness, I think back to everything that happened to us.

But that isn’t to say that I coped admirably with the affair, because I didn’t. It wasn’t just the circumstances, and the timing. My anger grew whenever Sergei repeated to me what Caitt had said about our relationship—when she knew perfectly well, of course, that he would do this.

‘She doesn’t understand why you’re upset because, as she said, it’s not as if I sleep with you anymore.’

I think this was the worst of her remarks. I was outraged that Sergei couldn’t see her sly cruelty, and I was also shocked that he’d discussed something so personal—and which had caused me great sadness—with someone as manipulative as Caitt.

I painted her character in the blackest terms that I could think of. Every time I did this, Sergei would storm out of the house. It became a regular occurrence. If I mentioned Caitt even in passing, he’d simply get up and leave—almost as if he’d been looking for an excuse to do so. I never asked him, when he returned—and he did always return—if he’d been to see her, because I had begun to shut off.

Only once did I ask him to tell me if he intended to leave permanently, and he looked straight through me and didn’t reply. I felt at that moment as if I didn’t exist.

It was strangely comforting. Nothing was real. So nothing mattered.

Lori was eventually transferred to a ward where she spent weeks going through an intensive rehabilitation process. She was still stuck in hospital, and desperate to go home. Eve and Lili almost went broke as they continued flying back and forth between London, Shanghai and Sydney, staying at the house on the peninsula with our parents.

Whenever they came back, I took the opportunity to ‘vanish’, booking cheap hotel rooms in the city and eating dinner in food courts, rather than go ‘home’ or stay with friends and have to admit what was happening. Lili and Eve always knew where I was, but nobody else did. At times Sergei seemed disturbed by my absences, but he never asked me where I disappeared to on these occasions. I suspect that he had decided, like me, that anything beyond the immediate moment was simply too difficult to deal with.

It was interesting that neither of us moved out of the house, even though ‘home’ had become an ambiguous word. But it was during this period that an incident occurred which I’ve never forgotten. It changed my perspective completely.

Late one Saturday afternoon, Sergei and I bumped into each other in the street outside our house. I was coming home, briefly. Sergei was going out. Both of us halted, uncertain whether to say anything to each other, or simply pass each other by.

He looked completely worn out. We both did. We had raged at each other ever since his confession, until eventually a sorrow set in. I felt I had no right to tell Sergei to end the affair even though by this time I knew, or thought I knew, the full extent of Caitt’s ruthlessness. I had no idea why Sergei continued to come home—eventually—every evening. Or why, if I was away, he rang me each night once he walked through our front door.

I said without anger that we seemed to be at an impasse, and that I was thinking of leaving him for good, because I felt that he wanted—needed—to be elsewhere. I added that, if he truly felt he would be happier with someone else at this stage of his life, he should follow his heart. I didn’t want him to feel obligated to me, or to stay with me through kindness. I wanted him to be happy, if there is such a thing. I wanted him to find peace.

Sergei listened without speaking. Then he said simply, ‘Can’t you wait for me, the way I waited for you?’

Perhaps he had been searching for an opportunity to say that to me. Perhaps, in our anger at each other, we’d kept missing the right moments to try and c

ommunicate. Although, far more likely, it was because we were spending so much time apart.

I didn’t know then how these words of his, too, would leave an echo. The softness that had been missing for so long from his face returned briefly and now, while I knew that he wouldn’t end the affair immediately, I sensed that Caitt’s hold over Sergei’s life—and mine—wouldn’t become permanent.

I got that drastically wrong, too, only not in a way that anyone could ever have predicted.

The footpath incident was the beginning of the end of Sergei’s affair, although something else happened a few weeks later that almost did persuade me to leave him for good.

I had been back working in the eyrie, and was walking through the city towards the Harbour Bridge mid-afternoon when I suddenly felt a sharp pain and started gasping for breath. Two alarmed passersby and a security guard helped me into a nearby medical centre where I was examined by a doctor and given blood tests. Apparently I was having a panic attack—a condition I knew barely anything about.

It was a bad one, so they said. I lay on a bed in a room in that medical centre for almost two hours, because I felt faint whenever I tried to sit up—and I tried to keep sitting up because the last thing I wanted was to be transferred to hospital. I’d had enough of hospitals for a lifetime! Eventually, I did feel much better, and a nurse asked if they could ring someone to come and collect me.

I insisted I felt well enough to leave without help and they let me go, somewhat doubtfully.

The noise of the traffic seemed louder than usual, and the light hurt my eyes. I had intended walking to Circular Quay, and then taking a ferry to McMahons Point. But I felt too tired even for this. I went into a cafe, and ordered a lemon squash and a tiramisu, for energy. And then I rang Sergei.

To his credit, he drove into the city immediately, parked illegally (as he told me later), and hurried into the cafe looking stricken. I avoided talking about what had happened, save for a brief conversation—for which I think he was thankful—and the moment we got home, he started getting organised to cook dinner while I rested.

That evening, after I’d taken the medication I’d been given and had gone back to lie on the bed, I heard Sergei’s phone ring. He lowered his voice while he was speaking and I knew that he must be giving Caitt an update. A few minutes later he came into the bedroom with a quizzical expression and asked me to show him the plasters that I should have on my arms—if I’d really had blood tests.

At that moment I truly hated both Caitt and Sergei, and I think Sergei realised it, although I was so spaced out from the medication that I merely pushed up my sleeves and showed him my arms. He had the grace to look ashamed for believing, as Caitt had obviously suggested, that I’d made up the whole story.

Thank god for those pills. I was unused to tablets of any kind, and these had what I regarded as a brilliant effect. After that brief flash of anger, all my emotions dissolved. For the first time in ages, I felt no anxiety, no sense of trepidation. Nothing. Now I understood how people could become hooked on prescription drugs. And because of that, I knew that first thing in the morning I should throw the rest of the tablets away, which I did—after a final, wistful look at the packet.

I kept just one pill aside.

I waited a week while trying to make up my mind about whether to just do it, and leave Sergei. Was I hoping that he would suddenly tell Caitt it was over and come home on a white horse, bearing caviar and vodka?

He went away for the weekend—I have no idea where—and on the Monday morning I got up, packed a few things and, shortly before midday, walked out of the house with my suitcase and laptop, not having a clue what I was going to do next. And not caring.

By late afternoon, when the pill—that last one—began to wear off, I stopped aimlessly walking around the city and went back to the eyrie, where I’d left my belongings. I couldn’t be bothered finding yet another cheap hotel for the night and, since the office included a tiny bathroom, the logical decision was to sleep on the small sofa crammed between desk and door, and to think about what to do next in the morning.

There was a little Japanese cafe in the street directly below. I ate there. My phone was switched off. I wondered what would happen if Sergei suddenly had another brain bleed, and immediately switched my phone back on. I rang him. The number rang out, so I switched my phone off again.

I ate there again the following night, when once again I was the only person dining alone. I didn’t mind. Nor did I wonder where Sergei was, or whether he’d even gone home. I liked the fact that the meal came with wonderful old chopsticks, rather than cheap wooden ones. I ate slowly. The food was delicious. The cafe owner bowed as I left.

Then I went back to the eyrie, where I thought how ridiculous it was to end a marriage in such a fashion, camping in a friend’s office in the city. Shouldn’t there be a more dramatic finale? What would Caitt do in the same circumstances? Perhaps I should ring her and ask.

I sat at the window for a while, battling despair, and then phoned my parents to ask about Lori, keeping my tone light and breezy. Afterwards, I went to sleep on the sofa, using a wrap that I’d thrown into my suitcase at the last minute as a blanket. At five in the morning, wide awake again, I opened my phone and found seven missed calls from Sergei.

That night we met for dinner in the Japanese cafe. Sergei had his old energy back. I saw it the moment he walked in. He looked refreshed and all the tiredness had gone from his face. Evidently my leaving had invigorated him. This was the new start he needed.

‘Where did you go?’ he demanded, the moment he sat down.

It was a totally unexpected opening line. Why did he suddenly care? As it happened, I’d slept for a second night in the eyrie, but I didn’t want him to know. I shrugged.

Sergei sighed, exasperated, but didn’t push for an answer. He asked the cafe owner for a menu, before launching straight into what he wanted to say. Caitt’s parents had bought a new house and in three weeks’ time they were having a housewarming party. It was going to be a big event, with all of Caitt’s family attending. As it happened, both Sergei and I had met Caitt’s parents once or twice at her Sunday lunches and we’d met many of her other relatives as well. Caitt wanted Sergei to go to the party as her partner.

Well, of course she did. I wasn’t surprised by Sergei’s announcement. I almost asked what he and Caitt were planning to buy her parents for a housewarming present. It was the perfect occasion for Caitt to introduce her new beau to her family. Or perhaps she wouldn’t need to say anything at all, since obviously I wouldn’t be there. The situation would speak for itself.

Fait accompli.

I wondered idly what the expression was in Russian.

‘I’m not going,’ said Sergei.

I looked away. What a comedy. Of course he was going. I didn’t need to hear what I assumed was about to follow: that Sergei would politely lament the end of our marriage and then, after some minutes, would come up with a hollow reason about why, after all, he should accept the invitation.

‘I told Caitt that I couldn’t go to the party, because you’re not invited.’

Sushi, or tempura? I could never decide. Once, in Tokyo, I’d eaten the best sushi in a bar in the very heart of the city, in one of the tiniest streets I’d ever seen, where the tram ran alongside people’s houses.

‘Zara? Are you listening at all? Caitt said that she wanted to invite you to her parents’ party as well, but that it was out of the question because you have a problem with her.’

I almost laughed. Truly, she was beyond belief.

Sergei was still waiting for my response.

‘Do you think it’s possible,’ I asked, ‘that she stands in front of the bathroom mirror and practises her lines?’

He considered this. ‘Yes. Perhaps she does,’ he eventually replied. And the ghost of a grin crossed his face.

We didn’t talk about Caitt after that. I actually felt her presence—for the first time—start to fade. Nor did I p

ress Sergei to end the affair, but I knew that it was only a matter of time.

After dinner we went our separate ways—Sergei, back to the house, me, upstairs to the eyrie. But we agreed that at the weekend, after I had been to see Lori, we would drive out of the city and spend three days together.

It was mid-May. We kept to our plan and went to an old hotel by a river that both of us loved—and finally, we started to talk to each other warily, and with curiosity, too. For one entire afternoon, we sat by the river in silence, and that evening we slept like exhausted travellers.

Then we went back to the city and, a day later, Sergei told Caitt that he wanted to remain a friend, but not a lover. He also told her that he wasn’t going to leave me. He went to see her, to tell her directly, and when he returned home he looked shaken. I could almost feel her fury following him through the front door.

‘She’s very angry with you,’ he said.

I had a thousand questions for Sergei. I asked none of them. I knew that we had to find our footing again with each other and I hoped that he would be able to gently put Caitt to one side.

I also knew that she would keep phoning him, and that he would still take her calls. It was the right thing to do and I knew that as well—despite initially rebelling against the idea of Sergei and Caitt remaining in contact. It was part of his character to treat people decently, although that may sound contradictory and perverse. He wouldn’t discard her. Sergei never discarded anyone. Old girlfriends. Caitt. Me.

There was one thing that I don’t think Caitt ever worked out, though. Sergei and I had something important in common. Neither of us was ‘good’ at infidelity; neither of us was a natural. Our respective uselessness at being able to cope with unfaithfulness was, I believe, one of the things that brought Sergei and me back together—for the time we had left.

Goody Two-Shoes

Goody Two-Shoes The Pearl Box

The Pearl Box And when you gone...

And when you gone... Stranger At The Other Corner

Stranger At The Other Corner My Young Days

My Young Days Harry's Ladder to Learning

Harry's Ladder to Learning Vice in its Proper Shape

Vice in its Proper Shape_preview.jpg) Promise (the curse)

Promise (the curse) The First Sexton Blake

The First Sexton Blake Golden Moments

Golden Moments Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3 The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Phebe, the Blackberry Girl

Phebe, the Blackberry Girl Stoned Immaculate

Stoned Immaculate Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3 The Wonder of War on Land

The Wonder of War on Land Breaking Bailey

Breaking Bailey The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience

The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience The Popular Story of Blue Beard

The Popular Story of Blue Beard The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service

The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs

Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3 Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories

Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories Two Yellow-Birds

Two Yellow-Birds Courtesans and Opium

Courtesans and Opium The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest

The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest Toots and His Friends

Toots and His Friends Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield

Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City

Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City A Picture-book of Merry Tales

A Picture-book of Merry Tales The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago

The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria

Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm

The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog

Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog The Story of the White-Rock Cove

The Story of the White-Rock Cove Grushenka. Three Times a Woman

Grushenka. Three Times a Woman Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself

Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself Falling in Love...Again

Falling in Love...Again The Colossal Camera Calamity

The Colossal Camera Calamity Child of the Regiment

Child of the Regiment Elimination Night

Elimination Night The Kingfisher Secret

The Kingfisher Secret Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise.

Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise. The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn

The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn Adventures of Bobby Orde

Adventures of Bobby Orde Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries

Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries When Love Goes Bad

When Love Goes Bad The Incest Diary

The Incest Diary Calling Maggie May

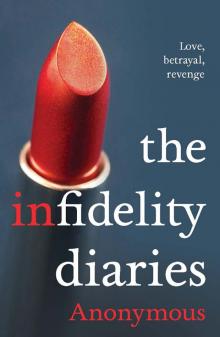

Calling Maggie May The Infidelity Diaries

The Infidelity Diaries Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) ARABELLA

ARABELLA The Eye of the Moon

The Eye of the Moon Dara

Dara THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake

THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake The Book of Death

The Book of Death The Book of David

The Book of David The Devil's Graveyard

The Devil's Graveyard The Book With No Name

The Book With No Name I Am A Lesbian

I Am A Lesbian Njal's Saga

Njal's Saga The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh Darling

Darling Tal, a conversation with an alien

Tal, a conversation with an alien Go Ask Alice

Go Ask Alice Aphrodizzia

Aphrodizzia The Campus Trilogy

The Campus Trilogy Augustus and Lady Maude

Augustus and Lady Maude Lucy in the Sky

Lucy in the Sky Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Pleasures and Follies

Pleasures and Follies The Red Mohawk

The Red Mohawk A Fucked Up Life in Books

A Fucked Up Life in Books Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) Astrid Cane

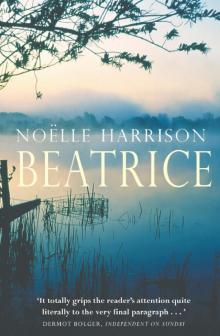

Astrid Cane BEATRICE

BEATRICE The Song of the Cid

The Song of the Cid