The Pearl Box Read online

Page 6

* * * * *

God hath given to man a short time here upon earth, and yet upon thisshort time eternity depends.--_Taylor_.

JANE AND HER LESSONS.

It is a mark of a good scholar to be prompt and studious. Such were thehabits of little Jane Sumner. She was the youngest of three sisters, andfrom her first being able to read, she was very fond of reading; and atschool her teacher became much interested in little Jane on account ofher interest in study, and the promptness she manifested in reciting herlessons. Jane had a quiet little home and was allowed considerable timefor study, although she had to devote some time in assisting her motherabout house.

There was a very fine garden attached to Mrs. Sumner's residence, whereshe took much pleasure in cultivating the flowers. In the centre of thegarden was built a summer house all covered over with grape vine. Thebroad leaves of the vine made a refreshing shade to it, and therebyshielded the warm sun from persons under it. This little summer houseJane frequently occupied for her study. In the picture you see her withbook in hand getting her lesson. She arose very early in the morning,and by this means gained much time.

Up in the morning early, By daylight's earliest ray, With our books prepared to study The lessons of the day.

Little Jane, for her industry and good scholarship, obtained quite anumber of "rewards of merit," which her schoolmates said she justlydeserved. There is one of them with these lines:

For conduct good and lessons learned, Your teacher can commend; Good scholarship has richly earned This tribute from your friend.

On one day, she came running home very much pleased with her card,which her teacher gave herself and her little sister Emma, for theirgood conduct and attention to their studies. The card contained theselines:

See, Father! mother, see! To my sister and me, Has our teacher given a card, To show that we have studied hard. To you we think it must be pleasant, To see us both with such a present.

Every good boy and girl will be rewarded, and all such as are studious,and respectful to their teachers, will always get a reward.

* * * * *

God never allowed any man to do nothing. How miserable is the conditionof those men who spend their time as if it were _given_ them, and notlent.--_Bishop Hall_.

HARVEST SONG.

Now the golden ear wants the reaper's hand, Banish every fear, plenty fills the land. Joyful raise songs of praise, Goodness, goodness, crowns our days. Yet again swell the strain, He who feeds the birds that fly, Will our daily wants supply.

CHORUS--

As the manna lay, on the desert ground, So from day to day, mercies flow around. As a father's love gives his children bread, So our God above grants, and we are fed.

* * * * *

Think in the morning what thou hast to do this day, and at night whatthou hast done; and do nothing upon which thou mayest not boldly askGod's blessing; nor nothing for which thou shalt need to ask hispardon.--_Anon_.

TELLING SECRETS.

There is a company of girls met together, and what can they be talkingabout. Hark! "Now I will tell you something, if you'll promise never totell," says Jane. "I will, certainly," replied Anne. "And will youpromise _never_ to tell a single living creature as long as you live?"The same reply is given, "_I will never tell_."

Now Jane tells the secret, and what is it? It turns out to be justnothing at all, and there is no good reason why every body should'ntknow it. It is this--"Lizzy Smith is going to have a new bonnet, trimmedwith pink ribbon and flowers inside." Anna thinks no more of her solemnpromise, and the first school-mate she meets, she opens the secret, witha solemn injunction for her not to tell. By and by the secret is allout among the girls--the promises are all broken. Now, children,remember your word--keep it true, and never make a promise which you donot intend to keep, and always avoid telling foolish secrets.

AGNES AND THE MOUSE.

One brilliant Christmas day, two little girls were walking towards aneighboring village, when they observed a little creature walking aboutthe road. "Surely," said Mary, "it is a large mouse;" and it did notseem to be afraid, so they thought from its tameness, it must be hungry."Poor little thing," said Agnes, "I wish I had something to give you."She took a few almonds from her pocket and went gently along towards themouse and put it close by its side. The mouse began to nibble, and soonfinished it. Agnes then put down two or three more, and left the mouseto eat its Christmas dinner. I think you would have enjoyed seeing themouse eating the almonds. I hope you will always be kind to poor dumbanimals. I have seen children who were cruel to dumb animals. This isvery wrong, and such children will never be respected, nor can theyexpect to be befriended.

THE TWO ROBINS.

A few summers ago I was sitting on a garden seat, beneath a fruit tree,where the works of nature look very beautiful. Very soon I heard astrange noise among the highest branches of the tree over my head. Thesound was very curious, and I began to look for the cause. I shook oneof the lower branches within my reach, and very soon I discovered twobirds engaged in fighting; and they seemed to gradually descend towardsthe ground. They came down lower and lower, tumbling over one another,and fighting with each other. They soon reached the lowest branch, andat last came to the ground very near me. It was with some difficultythat I parted them; and when I held one of them in each of my hands,they tried to get away, not because they were afraid of me but becausethey would resume the conflict. They were two young robins, and I neverbefore thought that the robin had such a bad spirit in its breast. Lestthey should get to fighting again, I let one go, and kept the otherhoused up for several days, so that they would not have much chance ofcoming together again.

Now, children, these two little robins woke in the morning verycheerful, and appeared very happy as they sat on the branch of the tree,singing their morning songs. But how soon they changed their notes. Youwould have been sorry to have seen the birds trying to hurt each other.

If children quarrel, or in any degree show an unkind temper, they appearvery unlovely, and forget that God, who made them, and gives them manyblessings, disapproves of their conduct. Never quarrel, but remember howpleasant it is for children to love each other, and to try to do eachother good.

* * * * *

Every hour is worth at least a good thought, a good wish, a goodendeavor.--_Clarendon_.

THE PLEASANT SAIL.

Down by the sea-coast is the pleasant town of Saco, where Mr. Aimes hasresided for many years. Once a year he had all his little nephews andnieces visit him. It was their holiday, and they would think and talkabout the visit for a long time previous to going there. Their uncletook much pleasure in making them happy as possible while they were withhim. He owned a pleasure sail boat which he always kept in good order.On this occasion he had it all clean and prepared for the young friends,as he knew they lotted much on having a sail. As his boat was small, hetook part of them at a time and went out with them himself, a shortdistance, and sailed around the island, and returned. In the picture yousee them just going out, with their uncle at the helm, while three ofthe nephews are on the beach enjoying the scene.

But I must tell you children to be very careful when you go on the waterto sail. There are some things which it is necessary for you to know, asa great many accidents occur on the water for the want of rightmanagement. When you go to sail, be sure and have persons with you whounderstand all about a boat, and how to manage in the time of a squall.Always keep your seats in the boat, and not be running about in it.Never get to rocking a boat in the water. A great many people have losttheir lives by so doing. Sailing on the water may be very pleasant andagreeable to you if you go with those who understand all about theharbor, and are skilled in guiding the boat on the dangerous sea.

THE SAILOR BOY.

Yarmouth is the principal trade s

eaport town in the county of Norfolk.Fishermen reside in the towns and villages around, and among the numberwas a poor man and his wife; they had an only son, and when ten yearsold his father died. The poor widow, in the death of her husband, lostthe means of support. After some time she said to her boy, "Johnny, I donot see how I shall support you." "Then, mother, I will go to sea," hereplied. His mother was loth to part with Johnny, for he was a good sonand was very kind to her. But she at last consented on his going to sea.

John began to make preparations. One day he went down to the beachhoping to find a chance among some of the captains to sail. He went tothe owner of one and asked if he wanted a boy. "No," he abruptlyreplied, "I have boys enough." He tried a second but without success.John now began to weep. After some time he saw on the quay the captainof a trading vessel to St. Petersburg, and John asked him if "a boy waswanted." "Oh, yes," said the captain, "but I never take a boy or a manwithout a character." John had a Testament among his things, which hetook out and said to the captain, "I suppose this won't do." The captaintook it, and on opening the first page, saw written, "_John Read, givenas a reward for his good behavior and diligence in learning, at theSabbath School_." The captain said, "Yes, my boy, this will do; I wouldrather have this recommendation than any other," adding, "you may go onboard directly." John's heart leaped for joy, as, with his bundle underhis arm, he jumped on board the vessel.

The vessel was soon under weigh, and for some time the sky was bright,and the wind was fair. When they reached the Baltic Sea a storm came on,the wind raged furiously, all hands were employed to save the vessel.But the storm increased, and the captain thought all would be lost.While things were in this state the little sailor boy was missing. Oneof the crew told the captain he was down in the cabin. When sent for hecame up with his Testament in his hand and asked the captain if he mightread. His request was granted. He then knelt down and read the sixtiethand sixty-first Psalms. While he was reading the wind began to abate,(the storms in the Baltic abate as suddenly as they come on.) Thecaptain was much moved, and said he believed the boy's reading was heardin Heaven.

THE BRACELET;

OR, HONESTY REWARDED.

At St. Petersburg, the birth day of any of the royal family is observedas a time of great festivity, by all kinds of diversions. When thevessel in which John Read shipped arrived, he was allowed to go on shoreto see the sport on that occasion. In one of the sleighs was a lady, whoat the moment of passing him lost a bracelet from her arm, which fell onthe snow. John hastened forward to pick it up, at the same time callingafter the lady, who was beyond the sound of his voice. He then put thebracelet into his pocket, and when he had seen enough of the sport, wentback to the ship.

John told the captain all about it, showing him the prize which he hadfound.

"Well, Jack," said the captain, "you are fortunate enough--these areall diamonds of great value--when we get to the next port I will sell itfor you." "But," said John, "It's not mine, it belongs to the lady, andI cannot sell it." The captain replied "O, you cannot find the lady, andyou picked it up. It is your own." But John persisted it was not his."Nonsense, my boy," said the captain, "it belongs to you." John thenreplied--"But if we have another storm in the Baltic," (see storypreceding.) "Ah me," said the Captain, "I forgot all about that, Jack. Iwill go on shore with you to-morrow and try to find the owner." They didso; and after much trouble, found it belonged to a nobleman's, lady, andas a reward for the boy's honesty, she gave him eighty pounds Englishmoney. John's next difficulty was what to do with it. The captainadvised him to lay it out in hides, which would be valuable in England.He did so, and on arriving at Hull, they brought one hundred and fiftypounds.

John had not forgotten his mother. The captain gave him leave of absencefor a time, and taking a portion of his money with him, he started forhis native village. When he arrived there, he made his way to her housewith a beating heart. Each object told him it was home, and broughtbygone days to his mind. On coming to the house he saw it was closed. Hethought she might be dead; and as he slowly opened the gate and walkedup the path and looked about, his heart was ready to break. A neighborseeing him, said, "Ah, John, is that you?" and quickly told him that hismother still lived--but as she had no means of support, she had gone tothe poor house. John went to the place, found his mother, and soon madeher comfortable in her own cottage. The sailor boy afterwards becamemate of the same vessel in which he first left the quay at Yarmouth.

NO PAY--NO WORK.

"Little boy, will you help a poor old man up the hill with this load?"said an old man, who was drawing a hand cart with a bag of corn for themill.

"I can't," said the boy, "I am in a hurry to be at school."

As the old man sat on the stone, resting himself, he thought of hisyouthful days, and of his friends now in the grave; the tears began tofall, when John Wilson came along, and said,--"Shall I help you up thehill with your load, sir?" The old man brushed his eyes with his coatsleeve, and replied, "I should be glad to have you." He arose and tookthe tongue of his cart, while John pushed behind. When they ascended thetop of the hill, the old man thanked the lad for his kindness. Inconsequence of this John was ten minutes too late at school. It wasunusual for him to be late, as he was known to be punctual and prompt;but as he said nothing to the teacher about the cause of his being late,he was marked for not being in season.

After school, Hanson, the first boy, said to John, "I suppose youstopped to help old Stevenson up the hill with his corn."

"Yes," replied John, "the old man was tired and I thought I would givehim a lift."

"Well, did you get your pay for it?" said Hanson, "for I don't work fornothing."

"Nor do I," said John; "I didn't help him, expecting pay."

"Well, why did you do it? You knew you would be late to school."

"Because I thought I _ought_ to help the poor old man," said John.

"Well," replied Hanson, "if you will work for nothing, you may. _No pay,no work_, is my motto."

"To _be kind and obliging_, is mine," said John.

Here, children, is a good example. John did not perform this act ofkindness for nothing. He had the approbation of a good conscience--thepleasure of doing good to the old man--and the respect and gratitude ofhis friends. Even the small act of benevolence is like giving a cup ofcold water to the needy, which will not pass unnoticed. Does any bodywork for nothing when he does good? Think of this, and do likewise.

THE TREE THAT NEVER FADES.

"Mary," said George, "next summer I will not have a garden. Our prettytree is dying, and I won't love another tree as long as I live. I willhave a bird next summer, and that will stay all winter."

"George, don't you remember my beautiful canary bird? It died in themiddle of the summer, and we planted bright flowers in the ground wherewe buried it. My bird did not live as long as the tree."

"Well, I don't see as we can love anything. Dear little brother diedbefore the bird, and I loved him better than any bird, or tree orflower. Oh! I wish we could have something to love that wouldn't die."

The day passed. During the school hours, George and Mary had almostforgotten that their tree was dying; but at evening, as they drew theirchairs to the table where their mother was sitting, and began to arrangethe seeds they had been gathering, the remembrance of the tree came uponthem.

"Mother," said Mary, "you may give these seeds to cousin John; I neverwant another garden."

"Yes," added George, pushing the papers in which he had carefully foldedthem towards his mother, "you may give them all away. If I could findsome seeds of a tree that would never fade, I should like then to have agarden. I wonder, mother, if there ever was such a garden?"

"Yes, George, I have read of a garden where the trees never die."

"A _real_ garden, mother?"

"Yes, my son. In the middle of the garden, I have been told, there runsa pure river of water, clear as crystal, and on each side of the riveris the _tree of life_,--a tree that never fades. That garde

n is_heaven_. There you may love and love for ever. There will be nodeath--no fading there. Let your treasure be in the tree of life, andyou will have something to which your young hearts can cling, withoutfear, and without disappointment. Love the Saviour here, and he willprepare you to dwell in those green pastures, and beside those stillwaters."

* * * * *

Every neglected opportunity draws after it an irreparable loss, whichwill go into eternity with you.--_Doddridge_.

YOUNG USHER.

You gave read of that remarkable man, Mr. Usher, who was Archbishop ofArmagh. I will tell you something about his early childhood. He was bornin Dublin, in the year 1580, and when a little boy he was fond ofreading. He lived with his two aunts who were born blind, and whoacquired much knowledge of the Scriptures by hearing others read theScriptures and other good books. At seven years of age he was sent toschool in Dublin; at the end of five years he was superior in study toany of his school fellows, and was thought fully qualified to enter thecollege at Dublin.

While he was at college he learned to play at cards, and he was so muchtaken up with this amusement that both his learning and piety were muchendangered. He saw the evil tendency of playing at cards, and at oncerelinquished the practice entirely. When he was nine years old, he hearda sermon preached which made a deep impression on his mind. From thattime he was accustomed to habits of devotion. He loved to pray, and hefelt that he could not sleep quietly without first commending himself tothe care of his Heavenly Father for protection. You see him in thepicture kneeling by his bed side, alone with God. When he was fourteenyears old, he began to think about partaking of the Lord's supper. Hethought this act to be a very solemn and important one, and required athorough preparation. On the afternoon previous to the communion, hewould retire to some private place for self examination and prayer. Whenhe was but sixteen years of age, he obtained such a knowledge ofchronology as to have commenced the annals of the Old and NewTestaments, which were published many years after, and are now a generalstandard of reference.

Goody Two-Shoes

Goody Two-Shoes The Pearl Box

The Pearl Box And when you gone...

And when you gone... Stranger At The Other Corner

Stranger At The Other Corner My Young Days

My Young Days Harry's Ladder to Learning

Harry's Ladder to Learning Vice in its Proper Shape

Vice in its Proper Shape_preview.jpg) Promise (the curse)

Promise (the curse) The First Sexton Blake

The First Sexton Blake Golden Moments

Golden Moments Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3 The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Phebe, the Blackberry Girl

Phebe, the Blackberry Girl Stoned Immaculate

Stoned Immaculate Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3

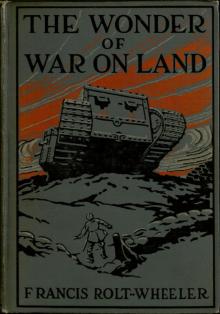

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3 The Wonder of War on Land

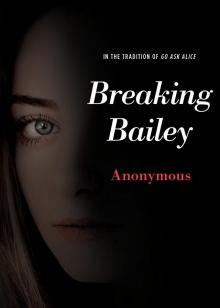

The Wonder of War on Land Breaking Bailey

Breaking Bailey The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience

The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience The Popular Story of Blue Beard

The Popular Story of Blue Beard The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service

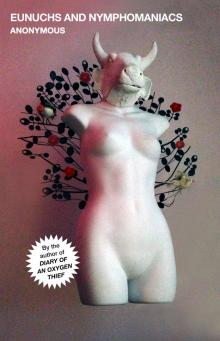

The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs

Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3 Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories

Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories Two Yellow-Birds

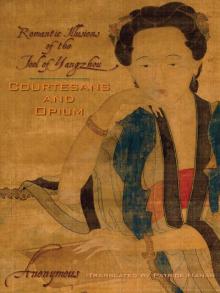

Two Yellow-Birds Courtesans and Opium

Courtesans and Opium The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest

The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest Toots and His Friends

Toots and His Friends Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield

Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City

Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City A Picture-book of Merry Tales

A Picture-book of Merry Tales The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago

The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria

Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm

The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog

Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog The Story of the White-Rock Cove

The Story of the White-Rock Cove Grushenka. Three Times a Woman

Grushenka. Three Times a Woman Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself

Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself Falling in Love...Again

Falling in Love...Again The Colossal Camera Calamity

The Colossal Camera Calamity Child of the Regiment

Child of the Regiment Elimination Night

Elimination Night The Kingfisher Secret

The Kingfisher Secret Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise.

Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise. The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn

The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn Adventures of Bobby Orde

Adventures of Bobby Orde Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries

Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries When Love Goes Bad

When Love Goes Bad The Incest Diary

The Incest Diary Calling Maggie May

Calling Maggie May The Infidelity Diaries

The Infidelity Diaries Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) ARABELLA

ARABELLA The Eye of the Moon

The Eye of the Moon Dara

Dara THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake

THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake The Book of Death

The Book of Death The Book of David

The Book of David The Devil's Graveyard

The Devil's Graveyard The Book With No Name

The Book With No Name I Am A Lesbian

I Am A Lesbian Njal's Saga

Njal's Saga The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh Darling

Darling Tal, a conversation with an alien

Tal, a conversation with an alien Go Ask Alice

Go Ask Alice Aphrodizzia

Aphrodizzia The Campus Trilogy

The Campus Trilogy Augustus and Lady Maude

Augustus and Lady Maude Lucy in the Sky

Lucy in the Sky Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Pleasures and Follies

Pleasures and Follies The Red Mohawk

The Red Mohawk A Fucked Up Life in Books

A Fucked Up Life in Books Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) Astrid Cane

Astrid Cane BEATRICE

BEATRICE The Song of the Cid

The Song of the Cid