Sight Unseen Read online

Page 5

“And you know the way?”

“Through this stretch of the caves, yes.”

The caves closest to Grand Avenue were wide and spacious, as promised. Bone dry, too, with a sterile, mineral scent. Alma and Driss walked with the torch lifted between them. The steady, dim light it cast, invisible by the surface, served them well in the pitch black.

After about a mile they reached a cavern. Seams of glowstone threaded through the living rock, lighting the vast space and all the people within. Alma saw several small huts, a cluster of canvas tents under a banner reading Smuggler’s Rest, with, in smaller letters beneath, Beds 5 coppers/night.

“Is that a joke?” Alma asked.

“It’s an inn,” answered Driss. “Catering to travelers who’ve come to the caves. Though I imagine some of their customers actually are smugglers. There are enough of them around here.”

And, most bizarre of all? Lil’ Spider’s Adventures—a children’s play park with little tunnels of sculpted mud to crawl through and a five-foot-high rock wall to climb.

“People take children here?” She hadn’t seen anything like this on her last trip through the caves.

“The kids insist. They all want to grow up to be spiders these days.” Driss shot Alma a strange, sad smile. “Or rebels.”

“And Ozias hasn’t put a stop to it?”

“How?” Driss pointed to the caves branching out from the huge cavern. “If they come, we just run into the caves. The soldiers will tear down all the buildings and a week later they’ll be back, same as they were before.”

“I suppose that’s what happens when evil is commonplace,” Alma mused. “The way we react to it becomes commonplace, too.”

A woman sold dumplings and “Spider’s bandanas” with a fringe of bright, clanking brass coins from a single brightly painted stall. Driss bought some of the dumplings, which she fried in a cast-iron pot before tipping them into a loosely-woven straw bowl. They were small and spicy enough to prompt another purchase: a ladle of milk to soothe the burn, which the woman poured directly into their mouths.

“This way.” Driss pointed to a cave, the mouth painted a bright red.

They left the concourse behind and plunged back into the dark. This new tunnel swerved and split, with only a few obscure signs to point the way—a gold coin pointing back to the market, stairs to indicate an exit. Others she couldn’t guess.

They reached a section that narrowed and narrowed. Alma and Driss turned sideways and shuffled along. After the expansive, open stretches of the Grand Avenue, it was strange to feel so cramped and closed in.

The tunnel broadened, finally—and shortened, too, so that Alma found herself crouching in a narrow dusty space, faced with the choice of continuing at a crawl or turning around and giving up.

“This is the worst of it,” Driss promised. “I can go first—”

“Better you don’t,” said Alma. “I’m smaller and you’re stronger. If I get stuck you’ll have a better chance of pulling me out.”

“You won’t get stuck.”

“Just in case, though.”

Alma took the torch and dropped to her hands and knees. She gritted her teeth and plunged ahead, trying not to think about wedging herself in like a cork in a bottle, about how she’d turn around if the passage ended abruptly, about being buried by falling rocks.

Absolutely none of those things crossed her mind. But when the narrow passage finally debouched her into a roomy cavern and she stood up on her own two feet again, she felt a little shaky.

Driss, too, seemed rattled, keeping his head averted and dodging the light.

“I thought you were sure we’d be fine,” Alma teased.

“I’m fine,” Driss said quickly.

Alma grinned. “Really?”

Driss blushed. “Of course.” He coughed, still not meeting her eyes. “This way.”

Their course trended upwards from there, which demonstrated how far they must have descended. Soon she began to see the long-legged, fat-bodied cave spiders that lived near the surface: the namesake for the human guides.

When one of the spiders skittered too close, Driss flinched away. Just as unthinkingly, Alma stepped on the thing.

“How do you stay so squeamish while leading a rebellion?” Alma asked. “I’d imagine you’d spend quite a bit of time in places like this.”

He shot her a strange look and then continued on, muscles in his jaw ticking.

Alma sighed. He’d been radiating discontent for hours now, ever since that odd moment when he’d coaxed her to lean on him and then dropped her. Or maybe the sucker-punch of warm charisma he’d thrown at her during the escape had been an oddity. Maybe this was normal for him. She had no idea; she didn’t know him.

Maybe he’d finally realized that he didn’t know her, either.

“You used to call me Little Lordling,” said Driss, voice tight. “You were teasing and I deserved it, but I hated it.”

“Little Lordling?” Alma repeated. And then, in disbelief, “Because you’re so dainty?”

“Because—” Driss scowled. “My father was Lord of the Vernal Marches.”

Alma’s jaw dropped.

“He’s dead,” Driss said harshly. “The lands and title were stripped from my family. They were executed.”

“So you’re the Lord of the Vernal Marches?”

“I told you. It’s gone.”

“But you would be. You were born to be.”

“I wasn’t the eldest.” He shook his head. “It doesn’t matter.”

It doesn’t matter. It was the sort of thing only a lord could say.

“Word and wish,” Driss muttered. “You don’t want to accept responsibility for a life you can’t remember—everything that you . . . no, that we did, together, the most important years of my—” He paused, then shifted direction. “You might try to understand that it’s almost the same for me. I was a lord once, yes. So long ago I hardly remember it. That it might as well have happened to someone else.”

“Except that you’re still a bit . . .”

He kicked idly at the smooth cave floor. “A bit.”

“I won’t call you Little Lordling,” said Alma. “Happy?”

He cast a sidelong glance at her, half suspicious and half hopeful.

“Breaking me out of a well-guarded prison earned you a bit of consideration,” Alma said. “Besides, I’m in no position to call you little. If anything, it would have to be the reverse.”

This, for some reason, completely stunned Driss. “You’re right. You’re shorter than I am.”

Alma laughed. “That surprises you?”

“When we met, you were taller than me.” His eyes widened. “I was fifteen. I must have grown a foot since then. But you’re . . . the same age as you were then.”

“The same age as you are now.”

“Yeah.” Driss grinned. “But this time you’re the little one.”

“I wouldn’t get any ideas.”

“Too late.”

Alma rolled her eyes. “How about you do something useful, like get us out of here?”

“This way . . .” Driss pointed, unnecessarily. The cavern only had two outlets, and they’d entered through one of them. “ . . . Little Lady.”

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

“Little Lamb.”

“I’ll turn you into a lamb if you keep it up.”

“Little Liar.”

Alma snorted.

A short while later, they emerged into the cool desert air, stars sparkling in a cloudless sky, cicadas chirping. Driss knocked at the door of a one-room, mud-brick hut and a young man answered, handsome and lean with long silky hair.

He blinked owlishly at his guests and then snapped to attention. “Commander.” He peered at Alma and then, after a whispered, “Word and wish,” he repeated the word: “Commander.”

“Have you got two all-in-ones ready to go?”

“Yes, of course. Let me show you . . .” The young ma

n led them back into the cave, to a stretch of bare rock wall where he shut his eyes, braced himself, and then . . . walked right through it.

“An illusion?” Alma marveled. “How many magicians do you have . . .?”

“One.”

She’d made it? But how? Alma swiped her hand through the air until she hit solid rock. She skimmed her fingers along the rough stone, tracing the seam. Even knowing where the two met, she couldn’t see a ripple or flaw anywhere.

“I don’t know how to do this,” she said. “I can’t even begin to guess how it was made.”

“You improved your craft over time,” said Driss. “Isn’t that to be expected?”

Perhaps. Yes. That didn’t make the evidence any less disorienting.

The young man stepped out of the illusion with a canvas backpack in each hand. “Is that all? Is there anything else I can do for you?”

Driss took both packs, handing one to Alma before swinging the other onto his back. “There’s a regiment camping nearby, isn’t there?”

“At the old trading post.”

“They’ll send someone to ask after us. When they do . . .”

“I haven’t seen you.”

“Good.” Driss motioned for the young man to lead the way out of the cave. “That’s all we need. Thanks for your help.”

“You can count on me,” the young man said fervently.

Alma looked back as they headed away from the little hut. A sign out front read Easy Access, Cheap! 50 silver.

“It’s a risk, but I think we should camp near the trading post,” said Driss. “I’d like to make sure the soldiers have taken our bait.”

“All right.”

Alma yawned. She’d been fine in the caves but now that she could see the sky again, she could hardly keep her eyes open.

“It’s not far.” Driss smiled at her, first tentative and then with more confidence. “You can do it.”

“Easy for you to say,” Alma grumbled. “Your feet aren’t made of lead.”

“Hey now. Those are dangerous words, coming from a magician.” Driss bumped his shoulder into hers, to show he was teasing, but their heavy backpacks collided and then bounced apart with enough momentum to throw Alma off balance. She wobbled. Driss made a startled noise, half-yelp and half-laugh, and caught her by the arm.

He laid a steadying hand on her hip and all of a sudden they were standing nose to nose, just inches apart. He smelled warm and musky and alive, a perfect antidote to the sterile mineral tang of the caves.

Driss jumped away. “So.” He tried to smile. “Almost there.”

Alma watched him trot ahead, smiling faintly. He was nervous. And . . . interested?

And building up quite a lead on her. With a deep sigh, she trudged after. Soon they reached a shallow escarpment that stretched from horizon to horizon. The highway ran parallel to the escarpment, a straight cut through the desert. They must have circled around it in the caves.

The trading post sprawled beside the road. Stables, outbuildings, niches in the wall facing the road where merchants could set up shop and a high, pointed arch leading to the central courtyard, where the well would be.

The stables were empty and so were the niches. All the trade in these parts had moved underground. The only people to use the once-thriving trading post these days would be Ozias’s men.

Driss pointed. “There.”

Alma followed the direction of his finger to a squat witch’s chimney. It had a few windows, so it had been hollowed into a dwelling at some point, but no door, which meant it had been abandoned.

There were several paths cut into the escarpment, of varying degrees of treacherousness. They chose one with divots hacked into the rock, a vague approximation of a staircase. They dropped their packs, to pick up at the bottom, and Driss carried the torch. He held it between them, leaving both her hands free as she followed behind, clinging to the uneven surface of the rock wall.

Two human-shaped silhouettes stood out against the peeling plaster of the trading post, floating several feet off the ground, necks crooked at unnatural angles. Citizens of Ozias’s Tenem grew accustomed to such displays, especially in the cities. In the end, that was what had driven Alma away from the capital. Not Gadi’s death but the spectacle that’d come after.

Who had died this time? A pauper who’d taken up residence in the vacant trading post? A miner who’d been slow to answer the soldiers’ questions? There was no crime too small. But as she and Driss drew closer, Alma saw that the hanged men wore military uniforms and boots polished to a mirror shine.

Mustache and Beady Eyes.

She almost vomited into the dirt. Word and wish. She knew those faces, she’d looked into their eyes. And now . . . their chests from shoulder to waist were bloody ruins, ribs exposed and cracked, skin and muscle pulped. They’d been executed by firing squad—by their own fellows—before they’d been hung from the walls.

“It’s not your fault,” said Driss.

“Of course it’s my fault.”

“Did compliance ever save anyone?” Driss asked, harshly. “Did obedience ever pay off, in the end?”

Alma shook her head.

“If the results are the same no matter what you do, then you’re not causing the problem.”

“But I knew this might happen,” said Alma. “And I did it anyway.”

Driss nodded. “And how many more of those villagers would have died if you hadn’t? How many more homes would have burned?”

“How many died before we arrived?” Alma responded. “That’s on us too. The soldiers would have left them alone if you hadn’t rescued me.”

“That’s on Ozias,” Driss snarled, stomping on ahead.

The ground floor of the abandoned witch’s chimney was round, with uneven hand-hewn walls and a domed ceiling. They climbed to the next floor on stairs carved into the living rock, each step dipping in the middle from many years of use. Alma steadied her palm on the gritty stone as she climbed to the next floor, empty like the first, and then up again to a third.

Driss took off one of his shoes and used it to sweep at the floor, without much effect. Alma sorted through the all-in-ones, which lived up to the name—each pack contained a bit of everything. A clean sarong, a medical kit, a knife, a canteen, strips of dried meat, nuts, salt. A purse which, on inspection, proved to be full of gold coins. With these supplies, they could wander toward the nearest city or into the remotest wilderness and manage pretty well, at least for a few days.

Alma extracted the compact bedrolls from the all-in-ones and laid them out on the floor. Then she offered Driss a strip of reddish-brown dried meat, took one for herself, and strolled over to the small window to gnaw at it. She had a good view of the trading post’s courtyard, lined with arcades, where soldiers went about their evening—washing at the well, mending clothes, smoking pipes and chatting.

Burn a village. March for miles through the hot desert sun. Kill a couple comrades. All in a day’s work for Ozias’s picked men. Now the time had come to relax and they settled right in, no qualms at all.

It wasn’t that she cared, particularly, that the two soldiers had died. Sympathy was a resource she couldn’t afford to spend freely. But Mustache and Beady Eyes had been put on display to send a message. To her, about her.

One she’d heard many times before: she was tainted and anything she touched was tainted.

Soon after Gadi had taken her on as an apprentice, he’d begun training her to run the games at his booth at the market. His favorite, thimblerig, involved setting three identical cups on a smooth board. When a customer wanted to play, Gadi ostentatiously placed a shiny marble underneath one cup and then shuffled all three quickly back and forth. When he stopped, the customer had to guess which cup hid the marble. If they guessed correctly, they would receive double their initial stake. If wrong, Gadi kept the coin himself.

But Gadi never really put a marble under the cups. Instead, he created the illusion of a marble. Wary customers,

expecting a con, would watch for a sleight of hand. It never came.

That was how Gadi had earned his pittance, and he’d expected Alma to follow in his footsteps. Alma had learned to blend the illusion spell into her patter, as Gadi did. You see this shiny marble here? She’d practiced shuffling the cups, faster and faster until they seemed to blur. And she’d grown more frustrated by the day.

“This is stupid,” she’d complained. “We could make so much more money. We could be rich.”

Even a child could fathom the possibilities. Why make an illusion of a marble when it could be a gold coin, instead? She could trade imaginary money for real food. And then real clothes and a real horse to ride right out of town, to start over a few miles away.

“We’d get caught,” Gadi had replied. “And then we’d get killed.”

To Gadi’s credit, nobody ever realized that he was a magician. He’d been arrested for petty thievery. Swept up in one of Ozias’s periodic purges, executed for tricking people with his silly games. Nobody ever saw the sleight of hand, but nobody believed he was playing fair, either.

In general, magicians attracted attention in one of two ways. Most often, a magician who’d been living incognito went mad. That usually entailed a few spectacular spells, followed by a grisly death at the hands of his neighbors.

The other way magicians attracted attention was by attaching themselves to a protector. Someone who had enough power to keep away the mobs, and a goal ambitious enough to justify the effort. Those partnerships could be the stuff of legends . . . or nightmares.

She, it seemed, fell into the latter group. It couldn’t be a coincidence that she’d fallen in with the last surviving member of a once-powerful family. What sort of bargain had she struck?

Alma turned back to Driss, who’d stretched out on his bedroll, one hand pillowed underneath his head, long legs loosely cocked. The mixture of confidence and pure animal grace in the pose took Alma’s breath. Word and wish, he was handsome.

“How did we meet?” she asked.

Goody Two-Shoes

Goody Two-Shoes The Pearl Box

The Pearl Box And when you gone...

And when you gone... Stranger At The Other Corner

Stranger At The Other Corner My Young Days

My Young Days Harry's Ladder to Learning

Harry's Ladder to Learning Vice in its Proper Shape

Vice in its Proper Shape_preview.jpg) Promise (the curse)

Promise (the curse) The First Sexton Blake

The First Sexton Blake Golden Moments

Golden Moments Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3 The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Phebe, the Blackberry Girl

Phebe, the Blackberry Girl Stoned Immaculate

Stoned Immaculate Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3

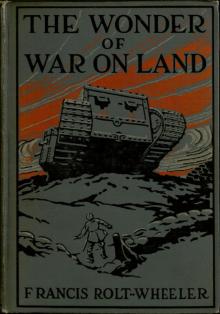

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3 The Wonder of War on Land

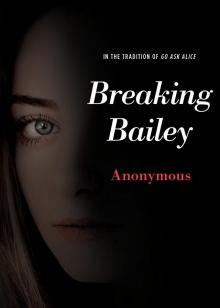

The Wonder of War on Land Breaking Bailey

Breaking Bailey The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience

The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience The Popular Story of Blue Beard

The Popular Story of Blue Beard The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service

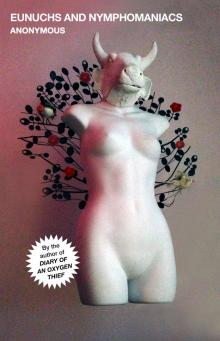

The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs

Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3 Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories

Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories Two Yellow-Birds

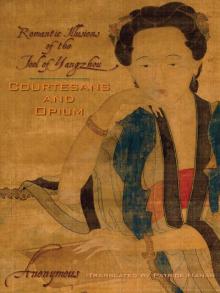

Two Yellow-Birds Courtesans and Opium

Courtesans and Opium The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest

The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest Toots and His Friends

Toots and His Friends Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield

Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City

Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City A Picture-book of Merry Tales

A Picture-book of Merry Tales The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago

The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria

Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm

The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog

Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog The Story of the White-Rock Cove

The Story of the White-Rock Cove Grushenka. Three Times a Woman

Grushenka. Three Times a Woman Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself

Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself Falling in Love...Again

Falling in Love...Again The Colossal Camera Calamity

The Colossal Camera Calamity Child of the Regiment

Child of the Regiment Elimination Night

Elimination Night The Kingfisher Secret

The Kingfisher Secret Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise.

Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise. The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn

The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn Adventures of Bobby Orde

Adventures of Bobby Orde Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries

Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries When Love Goes Bad

When Love Goes Bad The Incest Diary

The Incest Diary Calling Maggie May

Calling Maggie May The Infidelity Diaries

The Infidelity Diaries Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) ARABELLA

ARABELLA The Eye of the Moon

The Eye of the Moon Dara

Dara THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake

THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake The Book of Death

The Book of Death The Book of David

The Book of David The Devil's Graveyard

The Devil's Graveyard The Book With No Name

The Book With No Name I Am A Lesbian

I Am A Lesbian Njal's Saga

Njal's Saga The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh Darling

Darling Tal, a conversation with an alien

Tal, a conversation with an alien Go Ask Alice

Go Ask Alice Aphrodizzia

Aphrodizzia The Campus Trilogy

The Campus Trilogy Augustus and Lady Maude

Augustus and Lady Maude Lucy in the Sky

Lucy in the Sky Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Pleasures and Follies

Pleasures and Follies The Red Mohawk

The Red Mohawk A Fucked Up Life in Books

A Fucked Up Life in Books Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) Astrid Cane

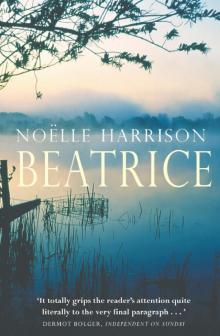

Astrid Cane BEATRICE

BEATRICE The Song of the Cid

The Song of the Cid