The Martyr of the Catacombs Read online

Page 3

CHAPTER III.

THE APPIAN WAY.

"Sepulchers in sad array Guard the ashes of the mighty Slumbering on the Appian Way."

Marcellus entered upon the duty that lay before him without delay. Uponthe following day he set out upon his investigations. It was merely ajourney of inquiry, so he took no soldiers with him. Starting forth fromthe Pretorian barracks, he walked out of the city and down the Appian Way.

This famous road was lined on both sides with magnificent tombs, all ofwhich were carefully preserved by the families to whom they belonged.Further back from the road lay houses and villas as thickly clustered asin the city. The open country was a long distance away.

At length he reached a huge round tower, which stood about two milesfrom the gate. It was built with enormous blocks of travertine, andornamented beautifully yet simply. Its severe style and solidconstruction gave it an air of bold defiance against the ravages of time.

At this point Marcellus paused and looked back. A stranger in Rome,every view presented something new and interesting. Most remarkable wasthe long line of tombs. There were the last resting-places of the great,the noble, and the brave of elder days, whose epitaphs announced theirclaims to honor on earth, and their dim prospects in the unknown life tocome. Art and wealth had reared these sumptuous monuments, and the piousaffection of ages had preserved them from decay. Here where he stood wasthe sublime mausoleum of Caecilia Metella; further away were the tombsof Calatinus and the Sarvilii. Still further his eye fell upon theresting-place of the Scipios, the classic architecture of which washallowed by "the dust of its heroic dwellers."

The words of Cicero recurred to his mind, "When you go out of the PortaCapena, and see the tombs of Calatinus, of the Scipios, the Sarvilii,and the Metelli, can you consider that the buried inmates are unhappy?"

There was the arch of Drusus spanning the road: on one side was thehistoric grotto of Egeria, and further on the spot where Hannibal oncestood and hurled his javelin at the walls of Rome. The long lines oftombs went on till in the distance it was terminated by the loftypyramid of Caius Cestius, and the whole presented the grandest scene ofsepulchral magnificence that could be found on earth.

On every side the habitations of men covered the ground, for theImperial City had long ago burst the bounds that originally confined it,and sent its houses far away on every side into the country, till thetraveler could scarcely tell where the country ended and where the citybegan.

From afar the deep hum of the city, the roll of innumerable chariots,and the multitudinous tread of its many feet, greeted his ears. Beforehim rose monuments and temples, the white sheen of the imperial palace,the innumerable domes and columns towering upward like a city in theair, and high above all the lofty Capitoline mount, crowned with theshrine of Jove.

But, more impressive than all the splendor of the home of the living wasthe solemnity of the city of the dead.

What an array of architectural glory was displayed around him! Therearose the proud monuments of the grand old families of Rome. Heroism,genius, valor, pride, wealth, everything that man esteems or admires,here animated the eloquent stone and awakened emotion. Here were thevisible forms of the highest influences of the old pagan religion. Yettheir effects upon the soul never corresponded with the splendor oftheir outward forms, or the pomp of their ritual. The epitaphs of thedead showed not faith, but love of life, triumphant; not the assuranceof immortal life, but a sad longing after the pleasures of the world.

Such were the thoughts of Marcellus as he mused upon the scene and againrecalled the words of Cicero, "Can you think that the buried inmates areunhappy?"

"These Christians," thought he, "whom I am now seeking, seem to havelearned more than I can find in all our philosophy. They not only haveconquered the fear of death, but have learned to die rejoicing. Whatsecret power have they which can thus inspire even the youngest and thefeeblest among them? What is the hidden meaning of their song? Myreligion can only hope that I may not be unhappy, theirs leads them todeath with triumphant songs of joy."

But how was he to prosecute his search after the Christians? Crowds ofpeople passed by, but he saw none who seemed capable of assisting him.Buildings of all sizes, walls, tombs, and temples were all around, buthe saw no place that seemed at all connected with the Catacombs. He wasquite at a loss what to do.

He went down into the street and walked slowly along, carefullyscrutinizing every person whom he met, and examining closely everybuilding. Yet no result was obtained from this beyond the discovery thatthe outward appearance gave no sign of any connection with subterraneanabodes. The day passed on, and it grew late; but Marcellus rememberedthat there were many entrances to the Catacombs, and still he continuedhis search, hoping before the close of the day to find some clue.

At length his search was rewarded. He had walked backward and forwardand in every direction, often retracing his steps and returning manytimes to the place of starting. Twilight was coming on, and the sun wasnear the edge of the horizon, when his quick eye caught sight of a manwho was walking in an opposite direction, followed by a boy. The man wasdressed in coarse apparel, stained and damp with sand and earth. Hiscomplexion was blanched and pallid, like that of one who has long beenimprisoned, and his whole appearance at once arrested the glance of theyoung soldier.

He stepped up to him, and laying his hand upon his shoulder said,

"You are a fossor. Come with me."

The man looked up. He saw a stern face. The sight of the officer's dressterrified him. In an instant he darted away, and before Marcellus couldturn to follow he had rushed into a side lane and was out of sight.

But Marcellus secured the boy.

"Come with me," said he.

The poor lad looked up with such an agony of fear that Marcellus was moved.

"Have mercy, for my mother's sake; she will die if I am taken."

The boy fell at his feet murmuring this in broken tones.

"I will not hurt you. Come," and he led him away toward an open spaceout of the way of the passers-by.

"Now," said he, stopping and confronting the boy, "tell me the truth.Who are you?"

"My name is Pollio," said the boy.

"Where do you live?"

"In Rome."

"What are you doing here?"

"I was out on an errand."

"Who was that man?"

"A fossor."

"What were you doing with him?"

"He was carrying a bundle for me."

"What was in the bundle?"

"Provisions."

"To whom were you carrying it?"

"To a destitute person out here."

"Where does he live?

"Not far from here."

"Now, boy, tell me the truth. Do you know anything about the Catacombs?"

"I have heard about them," said the boy quietly.

"Were you ever in them?"

"I have been in some of them."

"Do you know any body who lives in them?"

"Some people. The fossor stays there."

"You were going to the Catacombs then with him?"

"What business would I have there at such a time as this?" said the boyinnocently.

"That is what I want to know. Were you going there?"

"How would I dare to go there when it is forbidden by the laws?"

"It is now evening," said Marcellus abruptly, "come with me to theevening service at yonder temple."

The boy hesitated. "I am in a hurry," said he.

"But you are my prisoner. I never neglect the worship of the gods. Youmust come and assist me at my devotions."

"I cannot," said the boy firmly.

"Why not?"

"I am a Christian."

"I knew it. And you have friends, in the Catacombs, and you are goingthere now. They are the destitute people to whom you are carryingprovisions, and the errand on which you are is for them."

The boy held down his head and was silent. "I want you now to take me tothe entrance of the Catacombs."

"O, generous soldier, have mercy! Do not ask me that. I cannot do it!"

"You must."

"I will not betray my friends."

"You need not. It is nothing to show the entrance among the manythousands that lead down below. Do you think that the guards do not knowevery one?"

The boy thought for a moment, and at length signified his assent.

Marcellus took his hand and followed his lead. The boy turned away tothe right of the Appian Way, when he walked a short distance. Here hecame to an uninhabited house. He entered, and went down into the cellar.There was a door which apparently opened into a closet. The boy pointedto this, and stopped.

"I wish to go down," said Marcellus, firmly.

"You would not dare to go down alone surely, would you?"

"The Christians say that they do not commit murder. Why then should Ifear? Lead on."

"I have no torches."

"But I have some. I came prepared. Go on."

"I cannot."

"Do you refuse?"

"I must refuse," said the boy. "My friends and my relatives are below.Sooner than lead you to them I would die a hundred deaths."

"You are bold. You do not know what death is."

"Do I not? What Christian can fear death? I have seen many of my friendsdie in agony, and I have helped bury them. I will not lead you there.Take me away to prison."

The boy turned away.

"But if I take you away what will your friends think? Have you a mother?"

The boy bowed his head and burst into a passion of tears. The mention ofthat dear name had overcome him.

"I see that you have, and that you love her. Lead me down, and you shalljoin her again."

"I will

never betray them. I will die first. Do with me as you wish."

"If I had any evil intentions," said Marcellus, "do you think I would godown unaccompanied?"

"What can a soldier, and a Pretorian, want with the persecutedChristians, if not to destroy them?"

"Boy, I have no evil intentions. If you guide me down below I swear Iwill not use my knowledge against your friends. When I am below I willbe a prisoner, and they can do with me what they like."

"Do you swear that you will not betray them?"

"I do, by the life of Caesar and the immortal gods," said Marcellus,solemnly.

"Come along, then," said the boy. "We do not need torches. Follow mecarefully."

And the lad entered the narrow opening.

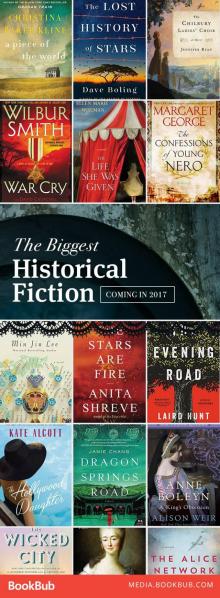

Goody Two-Shoes

Goody Two-Shoes The Pearl Box

The Pearl Box And when you gone...

And when you gone... Stranger At The Other Corner

Stranger At The Other Corner My Young Days

My Young Days Harry's Ladder to Learning

Harry's Ladder to Learning Vice in its Proper Shape

Vice in its Proper Shape_preview.jpg) Promise (the curse)

Promise (the curse) The First Sexton Blake

The First Sexton Blake Golden Moments

Golden Moments Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3 The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Phebe, the Blackberry Girl

Phebe, the Blackberry Girl Stoned Immaculate

Stoned Immaculate Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3 The Wonder of War on Land

The Wonder of War on Land Breaking Bailey

Breaking Bailey The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience

The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience The Popular Story of Blue Beard

The Popular Story of Blue Beard The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service

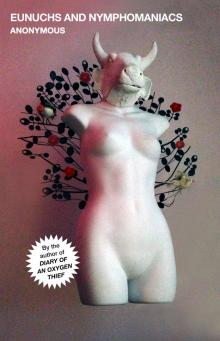

The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs

Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3 Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories

Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories Two Yellow-Birds

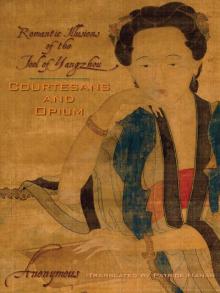

Two Yellow-Birds Courtesans and Opium

Courtesans and Opium The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest

The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest Toots and His Friends

Toots and His Friends Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield

Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City

Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City A Picture-book of Merry Tales

A Picture-book of Merry Tales The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago

The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria

Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm

The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog

Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog The Story of the White-Rock Cove

The Story of the White-Rock Cove Grushenka. Three Times a Woman

Grushenka. Three Times a Woman Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself

Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself Falling in Love...Again

Falling in Love...Again The Colossal Camera Calamity

The Colossal Camera Calamity Child of the Regiment

Child of the Regiment Elimination Night

Elimination Night The Kingfisher Secret

The Kingfisher Secret Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise.

Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise. The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn

The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn Adventures of Bobby Orde

Adventures of Bobby Orde Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries

Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries When Love Goes Bad

When Love Goes Bad The Incest Diary

The Incest Diary Calling Maggie May

Calling Maggie May The Infidelity Diaries

The Infidelity Diaries Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) ARABELLA

ARABELLA The Eye of the Moon

The Eye of the Moon Dara

Dara THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake

THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake The Book of Death

The Book of Death The Book of David

The Book of David The Devil's Graveyard

The Devil's Graveyard The Book With No Name

The Book With No Name I Am A Lesbian

I Am A Lesbian Njal's Saga

Njal's Saga The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh Darling

Darling Tal, a conversation with an alien

Tal, a conversation with an alien Go Ask Alice

Go Ask Alice Aphrodizzia

Aphrodizzia The Campus Trilogy

The Campus Trilogy Augustus and Lady Maude

Augustus and Lady Maude Lucy in the Sky

Lucy in the Sky Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Pleasures and Follies

Pleasures and Follies The Red Mohawk

The Red Mohawk A Fucked Up Life in Books

A Fucked Up Life in Books Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) Astrid Cane

Astrid Cane BEATRICE

BEATRICE The Song of the Cid

The Song of the Cid