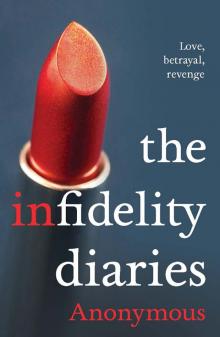

The Infidelity Diaries Read online

Page 3

It wasn’t the dust that made the day so memorable, though. Nor was it the moment when Sally took the photo of the three of us on the terrace. It was what came later.

Sergei announced that he was going off to say hello to our host. He had to hurry to catch up with Michael, who was already heading back towards a door at the rear of the house, from where he’d originally appeared.

Caitt, who hadn’t taken her eyes off Sergei, seemed about to follow him down into the garden when she was hailed by a woman with very short, bright red hair who had just walked through the French doors onto the terrace.

‘Tobie! You’re just in time!’ Caitt exclaimed, beckoning the newcomer over.

‘In time for what?’ queried the redhead, who was wearing a tennis dress, or something very similar. It was white, it was short, and it showed off her legs.

‘Just in time to keep Zara occupied,’ replied Caitt.

‘Zara, meet Tobie,’ she added. ‘My very good friend and genius computer consultant.’

Tobie chuckled, as if Caitt had said something funny.

‘Not anymore,’ she said obscurely. ‘Hi, Zara. I saw you arriving. Your husband is very handsome. Caitt told me about him when she got back from Thailand.’

Her voice, smooth as silk, was filled with amusement.

I said nothing.

‘Caitt and I go way back,’ Tobie continued, after exchanging looks with her friend. ‘We used to go on holidays together and chase men. We didn’t mind if they were married or not. Remember that summer in Sicily, Caitt?’

‘Do I!’ exclaimed Caitt, and burst into laughter.

I saw Sergei glance in our direction. He was talking to Joe and Sally. All three were drinking champagne and I wondered where Michael was. I needed a drink, too! At exactly that moment, Caitt’s husband walked through the French doors carrying more champagne and a couple of glasses, which he placed on a small table that had been set up on the terrace.

Caitt, who had her back turned to the French doors and seemed unaware of her husband’s presence, grabbed Tobie’s hand—and the pair of them took a step closer to me like two spiteful puppets.

‘Tobie and I have a history of fishing for men. We catch them, play with them and then we throw them back,’ she chanted.

‘You never throw them back,’ said Tobie, with emphasis. ‘You keep reeling them back in.’

Striking a pose she began singing softly. ‘Row, row, row our boat, gently down the stream. Merrily, merrily, merrily . . .’

Life is but a dream.

‘I can get any man that I want with a snap of my fingers,’ said Caitt with a swagger.

The atmosphere had changed. Something unpleasant was happening.

Tobie was grinning, but Caitt’s whole demeanour had altered. She had become scornful and hard, and she repeated the line almost in anger.

‘I can get any man that I want with a snap of my fingers!’

Then, just as suddenly, her laughter returned; flicking her hair back over her shoulders, she turned and walked down into the garden with Tobie in tow. Just before she reached Sergei, she looked back at me and briefly we stared at each other. At that moment I saw a woman standing in sunlight who seemed perfectly ordinary; perhaps, for a few seconds, she was the person she’d once been.

The sensation was very real, and made me wonder—not just then, but several times in the future—whether something had happened to Caitt earlier in her life, which had turned her into a predator.

I could have asked her, of course. Sometimes, when we were together, I sensed an underlying anxiety, a fear, an uncertainty about everything.

But I never did ask—and maybe that’s why she showed me no mercy.

There were many more Sunday lunches at Caitt’s. Sergei and I became a fixture at these feasts in the garden, until Caitt’s invitations to us as a couple dried up. But the first lunch was easily the most memorable.

When she said that she could get any man that she wanted with a snap of her fingers, Caitt was being deadly serious in exactly the same way that she had been in Phang Nga Bay when she performed her come-hither routine in the canoe.

Every woman that I know, including my sisters, Lili and Eve, would only make such a remark as a joke. I was still musing over the incident when Michael came over and handed me a glass of bubbly and said, ‘This is champagne! You drink it!’

He was friendly and funny, and completely different to Caitt; however, as we chatted about Thailand, I wondered what he had made of the scene that had just taken place on the terrace. I was also conscious that we were both watching his wife as she played up to Sergei at the edge of the lawn. When all of a sudden Caitt took Sergei’s arm and led him away from the others towards the ground floor of the house, Michael paused mid-sentence before continuing with what he’d been saying.

A few minutes later, Caitt and Sergei walked out onto a long upstairs balcony running the length of the house.

I glanced at Michael. ‘That’s the balcony off our bedroom,’ he said casually, his expression unreadable.

I think there’s a good chance that Caitt plotted the balcony scene even before she left Thailand—because when she took a step forwards and held up a small object that flashed in the sun, I suddenly understood the point of the exercise.

At the sound of the dinner bell ringing from above, all the guests in the garden looked up.

‘Hello, everyone. Finish your bubbly, because very shortly we’re serving lunch!’ she cried, once again linking arms with Sergei.

There was laughter and a scattering of applause. Caitt reacted to this by taking a bow. But the joke was on her unsuspecting audience, because she was thanking them for something entirely different.

An image had just been created of Caitt and Sergei that would stay etched in people’s minds.

Their first official appearance as a couple.

The garden setting may not have been as spectacular as Phang Nga Bay although, in the bright sunlight that Sunday, everything seemed to have taken on extra dramatic appeal: the long wooden table, already set with wineglasses and plates, the deckchair in front of the Japanese bamboo.

As the buzz of conversation resumed below them, Caitt and Sergei left the balcony; shortly afterwards, Sergei came back out onto the terrace. Caitt, he said, was preparing pasta for lunch.

Michael went off to help her, and we joined Joe and Sally on the lawn.

I assumed that Caitt would relax after the triumph of her balcony scene. But I assumed wrongly.

At about the same time that everyone began to make a move towards the table, our hostess suddenly appeared with Tobie and Michael—all of them holding large bowls of pasta—and planted herself in front of Sergei. ‘I want you to sit with me at the head of the table,’ she said, handing him the huge bowl of linguine in her hands.

‘Oh dear!’ exclaimed Tobie in a loud voice. ‘Where will you sit, Zara?’

At this, Sergei turned and gestured to me to join him—whereupon Caitt, who had already led him over to their seats, called out with a great show of solicitousness, ‘Oh, Zara, you don’t mind if I sit next to Sergei, do you? Will you be okay on your own?’

Even Sally, a scientist with an academic’s dreamy demeanour—I constantly teased her about being away with the fairies—raised incredulous eyebrows when Caitt said this, and I think Caitt realised that she’d just made a mistake.

I didn’t need to sit next to Sergei; he didn’t need to sit next to me. I wasn’t at all concerned about ‘where’ I would sit. Such an overt display of nastiness was instructive, although I was surprised at Caitt’s apparent lack of concern about how others might regard such an obvious act of malice.

And perhaps I was making too much of the entire incident, since it seemed doubtful that anyone else took much notice of what had just happened. Most of those present, nearly all of whom turned out to be members of Caitt’s extended family, were too busy talking.

‘Zara, there’s a seat here,’ said Sergei, tapping the chair o

n his left. ‘Come on!’

I didn’t look at Caitt as I sat down next to my husband although, when I did glance her way, she was not looking pleased. By now everyone was sitting down and helping themselves to the pasta. Tobie seated herself on the opposite side of the table to me and, to my surprise, since I assumed she was there to cause mischief, promptly launched into an entertaining story about her new job as a tour guide for a company specialising in trips to the Baltic Republics.

Caitt tried—unsuccessfully—to distract Sergei’s attention. But my husband, naturally, wanted to tell the story of how he and I had met en route to the Estonian capital when it was still under Kremlin control—and how I’d never made the rendezvous with the Swede.

‘Of course, once she’d met me she forgot all about him,’ Sergei added facetiously, leaving out the real facts of the story. ‘Besides, Swedes can’t compete with Russians in the bedroom.’

‘I’ll never know,’ I commented, equally facetiously, at which point Caitt knocked over a bottle of red wine she’d just opened.

It was Tobie who jumped up and dashed off to find something with which to mop up the puddles of pinot between our bowls of seafood linguine, lemon rissoni and smoked salmon fusilli. So much for Caitt’s concern about Sergei’s cholesterol, I thought—although it didn’t seem wise to say this aloud.

‘What a waste of good wine, Caitt,’ I said cheerfully, and was rewarded with a furious look from our hostess.

‘Yes, it is,’ agreed Sergei, getting to his feet. ‘I’ll go and fetch a couple more bottles.’

That was the first and last time Sergei and I sat together at one of Caitt’s Sunday lunches. There were place cards at the second lunch we went to—and the third, and the fourth. On each occasion I was put safely out of the way at the far end of the table, but at the third lunch, Caitt put me next to a relative of hers, a single man who’d been divorced for a number of years and who, she said suggestively while introducing us, was looking for a new relationship.

At the end of the afternoon, after he’d left, she inquired whether he had taken my phone number.

There were no witnesses to this scene. There never were during those moments—and there were several—when Caitt allowed me glimpses of the twist in her personality. It’s part of the reason why I damn Caitt in this story far more than I do Sergei—because he did not have a poisonous nature and the cynicism he increasingly displayed towards life was partly caused by the damage that I did early on to our relationship. I’m certain of this.

The morning after I’d admitted to having an affair, I woke up next to him and saw to my shock that he was weeping. I’ll never forget it. Nor what he said.

‘What a waste.’

I am certain that it was this fatalism that in part drove his ultimate infatuation with Caitt. Sergei was a good man, who had once loved me unconditionally. My infidelity was his undoing.

To this day I can’t decide whether Caitt’s malevolence was due to some sort of desperation, or despair about how her life had played out, or whether she got a kick out of trying to unsettle me because that was just part of her nature. Even when she reached the stage of not caring anymore about crossing the line and making it obvious that she was throwing herself at Sergei, she was careful to keep in check the venom that I suspected she kept in reserve for any woman who got in her way—and which, in the end, she was unable to control.

I doubt that I was the first woman to have found herself in Caitt’s way. In fact, I know it. But to provide any more details would be to betray someone who asked me never to repeat what she told me because, as she put it, she escaped from Caitt’s grip—even if her own husband didn’t.

All I can say is that this woman, who was married to a friend of Joe’s, warned me about Caitt the first time we met. ‘Be very careful before you let that one into your house,’ she told me quietly.

Four years after that particular conversation, one sad evening as I was walking towards the large For Sale sign outside our house, I thought I caught a glimpse of the same woman in a car driving away down the street. Then, on the doorstep, I found a beautiful bunch of flowers with long stems; I particularly remember the long stems because I had to search out a vase in the packing.

There was no note with the flowers. But I knew who had left them. And why.

The Sunday lunches became such a regular event that we soon structured our weeks around them. I didn’t make a fuss about going to them, because I suspected that Caitt was hoping I would, and that any such reluctance on my part would play into her hands. My sister Lili, who lived in London and came to visit us in March, missed one of the lunches by only a day, because her departure date was a Saturday. This was probably fortunate, for while she was in Sydney she would ‘meet’ Caitt, without having a clue who she was—and would instinctively loathe her.

Lili came on her own, leaving her husband, Will, behind in London. He’d begged off the visit, pleading pressure of work. Lili and I joked in our emails to each other that, obviously, he had never recovered from his first visit to Australia, years earlier, when, looking increasingly haggard, he never stopped complaining about the noisiness of Australian birds at the crack of dawn.

The night before Lili was due to arrive, Sergei and I had our first argument about Caitt.

I had decided to have a break from work so I could spend time with my sister, and at breakfast that morning Sergei had suggested that the two of us should meet at the little wine bar a few streets away from our house where he met Joe most evenings after work for a glass of wine on the way home.

‘It would be nice if you came with me for a change,’ he added pointedly.

So I said yes, of course I would come—aware that I’d been spending long hours in my home office, reading through material for a new biography that my publisher was thinking of commissioning me to write.

The first person I saw when we walked into the wine bar was Caitt.

‘There’s Caitt,’ I said, somewhat idiotically.

‘Yes, she started coming to the wine bar a while back,’ replied Sergei. ‘We have a drink together most evenings.’

Caitt turned around at that moment and her dismayed expression told me everything. This was her territory with Sergei. I was the intruder. How dare I come here?

‘And that’s Clara,’ said Sergei, as one of the women that Caitt had been talking to, turned around at the same time. ‘She’s one of the speech pathologists Caitt works with.’

‘I didn’t know you’d met Caitt’s colleagues,’ I commented. ‘So they’ve just started coming to the wine bar as well?’

Before Sergei could reply, and before Caitt could stop her, Clara came over to where we were standing.

‘Hi, Sergei,’ she said, and added curiously, ‘Who’s this?’

‘This is Zara,’ said Sergei.

We shook hands. I had a fairly good idea what Clara would say next.

‘How do you two know each other?’

‘I’m married to Zara,’ said Sergei, genuinely surprised.

Clara glanced towards Caitt. ‘But I thought . . .’

She didn’t finish the sentence.

A couple of people I knew from the publishing industry were at the other end of the wine bar, and I thought this might be a good moment to go and talk to them. So I did. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Caitt approach Sergei, embrace him briefly, and then leave. Clara left soon afterwards, after throwing a few more questioning glances my way.

‘It seems that you and Caitt are regarded as a couple,’ I said evenly, once we were back in the car, driving home.

‘Not at all,’ replied Sergei. ‘It was just a misunderstanding. I always tell people about you.’

I knew that to be true. Sergei did tell people about me. But nor could I overlook Clara’s reaction. It was blindingly obvious, I persisted, that Caitt was letting people think that they had a relationship.

The conversation went nowhere. Sergei refused to countenance the idea that Caitt was doing any such

thing. ‘Why would I ask you to come to the wine bar with me, if that was happening?’ he asked. Sergei had a point, but giving in at this point wasn’t possible.

‘Because you’re naive,’ I answered. ‘You can’t see what’s happening. Caitt is bringing her friends to the wine bar and introducing them to you, because she’s trying to draw you into a life that’s separate to the one you have with me.’

‘Then you should come with me to the wine bar more often,’ retorted Sergei, logically enough.

We spoke in monosyllables to each other for the rest of the evening.

However, by the time Lili arrived the next day, we’d forgotten our quarrel and the three of us spent Lili’s first night in Sydney—a Monday—sitting up late, drinking champagne and talking about old times. When Sergei eventually went off to bed, Lili and I decided to ring our other sister, Eve, who lived in Shanghai. But the phone switched to voicemail and we left a drunken message instead.

We discussed ringing Lori, our older sister. But we knew that we wouldn’t. And besides, she probably wouldn’t pick up the phone. Lori led a quiet, reclusive life on her own in a small country town outside Sydney where she worked for a Christian charity organisation. She had kept herself at a distance from the rest of the family for years, a situation that saddened my parents although ever since Lori had joined a bizarre religious group in her twenties, she had been a difficult person to get on with. She stayed with the group for almost a decade before departing abruptly—giving no reasons—and moved to the town where she had lived ever since. Eve, Lili and I had all gone to see her on separate occasions, but it was obvious that Lori preferred her own company and after a while we had all stopped making the effort, opting to ring her occasionally instead. Lori never rang anyone. She remained aloof.

Goody Two-Shoes

Goody Two-Shoes The Pearl Box

The Pearl Box And when you gone...

And when you gone... Stranger At The Other Corner

Stranger At The Other Corner My Young Days

My Young Days Harry's Ladder to Learning

Harry's Ladder to Learning Vice in its Proper Shape

Vice in its Proper Shape_preview.jpg) Promise (the curse)

Promise (the curse) The First Sexton Blake

The First Sexton Blake Golden Moments

Golden Moments Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 2 of 3 The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Phebe, the Blackberry Girl

Phebe, the Blackberry Girl Stoned Immaculate

Stoned Immaculate Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 3 of 3 The Wonder of War on Land

The Wonder of War on Land Breaking Bailey

Breaking Bailey The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience

The Little Girl Who Was Taught by Experience The Popular Story of Blue Beard

The Popular Story of Blue Beard The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service

The Life Savers: A story of the United States life-saving service Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs

Eunuchs and Nymphomaniacs Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3

Hildebrand; or, The Days of Queen Elizabeth, An Historic Romance, Vol. 1 of 3 Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories

Kitty's Picnic, and Other Stories Two Yellow-Birds

Two Yellow-Birds Courtesans and Opium

Courtesans and Opium The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest

The Emigrant's Lost Son; or, Life Alone in the Forest Toots and His Friends

Toots and His Friends Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield

Fast Nine; or, A Challenge from Fairfield Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City

Ned Wilding's Disappearance; or, The Darewell Chums in the City A Picture-book of Merry Tales

A Picture-book of Merry Tales The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago

The Trail of The Badger: A Story of the Colorado Border Thirty Years Ago Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria

Peter Parley's Visit to London, During the Coronation of Queen Victoria The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm

The Rainbow, After the Thunder-Storm Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog

Arthur Hamilton, and His Dog The Story of the White-Rock Cove

The Story of the White-Rock Cove Grushenka. Three Times a Woman

Grushenka. Three Times a Woman Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself

Adventures of a Squirrel, Supposed to be Related by Himself Falling in Love...Again

Falling in Love...Again The Colossal Camera Calamity

The Colossal Camera Calamity Child of the Regiment

Child of the Regiment Elimination Night

Elimination Night The Kingfisher Secret

The Kingfisher Secret Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise.

Left to Ourselves; or, John Headley's Promise. The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn

The Island of Gold: A Sailor's Yarn Adventures of Bobby Orde

Adventures of Bobby Orde Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries

Twain, Mark: Selected Obituaries When Love Goes Bad

When Love Goes Bad The Incest Diary

The Incest Diary Calling Maggie May

Calling Maggie May The Infidelity Diaries

The Infidelity Diaries Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Diary of an Oxygen Thief (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) ARABELLA

ARABELLA The Eye of the Moon

The Eye of the Moon Dara

Dara THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake

THE ALTAR OF VENUS: The Making of a Victorian Rake The Book of Death

The Book of Death The Book of David

The Book of David The Devil's Graveyard

The Devil's Graveyard The Book With No Name

The Book With No Name I Am A Lesbian

I Am A Lesbian Njal's Saga

Njal's Saga The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh Darling

Darling Tal, a conversation with an alien

Tal, a conversation with an alien Go Ask Alice

Go Ask Alice Aphrodizzia

Aphrodizzia The Campus Trilogy

The Campus Trilogy Augustus and Lady Maude

Augustus and Lady Maude Lucy in the Sky

Lucy in the Sky Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Pleasures and Follies

Pleasures and Follies The Red Mohawk

The Red Mohawk A Fucked Up Life in Books

A Fucked Up Life in Books Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries)

Chameleon On a Kaleidoscope (The Oxygen Thief Diaries) Astrid Cane

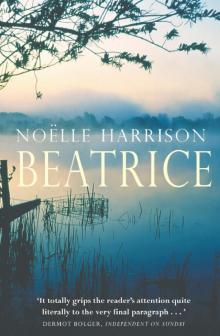

Astrid Cane BEATRICE

BEATRICE The Song of the Cid

The Song of the Cid